Arty Appetite: Lee Miller at Tate Britain

Every great actor knows how to track a camera lens. For Lee Miller — photographer, actor, war reporter and model — this was the role of a lifetime. But to keep her contained to the viewfinder of those who shot or directed her denies the twentieth-century trailblazer her most impressive accomplishment: knowing exactly where to direct the lens of her own penetrating gaze. Throughout Tate Britain’s retrospective of two hundred and fifty prints, Miller straddles the role of observer and observed — a duality that is clearest in her early editorial writing for Vogue, as seen in an article that sits against a shot she modelled for menstrual pads. But what could separate her out into fragmented roles instead makes up the inexplicable artistry and inimitable brand of Lee Miller as a creative, self-possessed whole.

Inside the exhibit’s first room, it’s difficult not to feel at the mercy of her scrutiny. A high vaulted ceiling with walls picked out in grey makes it seem as though visitors have been corralled into the belly of a monumental camera, while iterations of Miller sit dotted about the room. From dreamy, editorialised shots by Arnold Genthe to Man Ray’s 1929 portrait complete with Space Age glasses, Miller transforms under the lenses of her friends and collaborators. Supposing anything to be outside Miller’s skillset is quickly disproven as she transforms once again into an old Hollywood glamour puss, androgynous and dramatic in leisure wear and hazy in a self-portrait for Vogue. There’s something statuesque about Miller’s brand of beauty — a distance and an aspirational stylishness that shuts out those who try to neatly piece her together.

It’s fitting, then, that Miller starred in episode two of Jean Cocteau’s Le Sang d’un Poète as a marble figure that encourages Cocteau’s protagonist to walk through a mirror, which guides him to a hotel. It’s as though we too are transported when the next room’s candy floss walls come into focus. Here, Miller experiments with a more sensual gaze — variations on a Grecian nude culminate in a chopped-off torso in the only signed version of the photo.

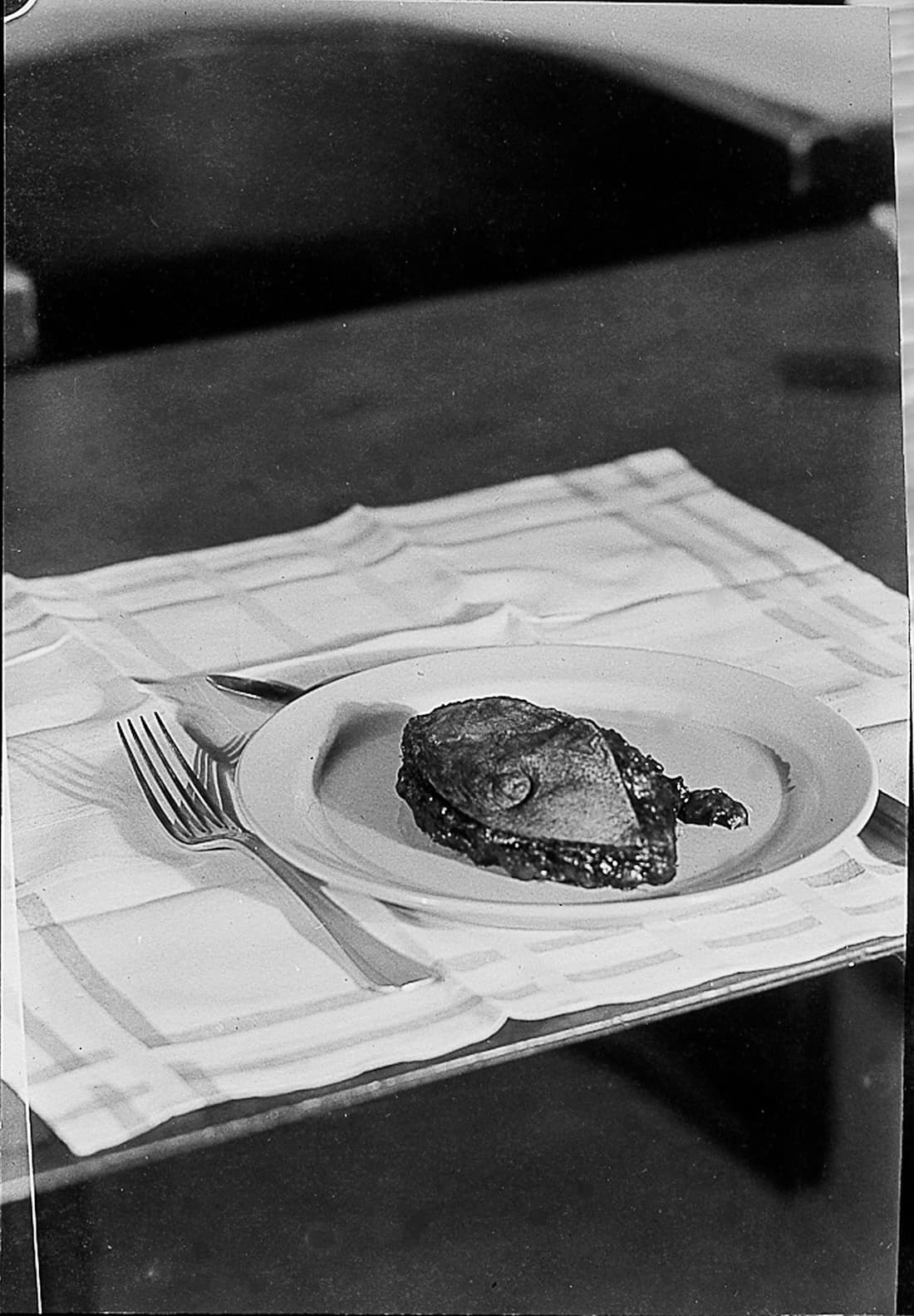

Her talent for composition and unique creative instinct that have won her such fame is perhaps best contained in her surrealist take on a dinner setting, Untitled (Severed Breast from Radical Surgery). From this point, the exhibition tracks Miller’s progress through surrealist visions of staircases in Cairo, afternoons spent alongside Leonora Carrington in South-West England and Britain in the throes of war.

To talk about Lee Miller’s work is, of course, to talk about war. But beyond her famed photography, Miller’s original reports and emphatic refute to rumours that the concentration camps were nothing but a hoax — evidenced best in the enclosed room titled ‘Believe It’. Miller captures it all in horrific, brutal detail. So, too, does she examine the other side of war — something the photographer found particularly repugnant — namely, the relative excess and leisure-filled days of German citizens.

Just as the severed breast holds your attention, the focus of Miller’s wider war reporting anchors itself to Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub. This talent for recognising and capturing the core of an emotion, an experience or a wider theme of injustice is perfectly distilled into this single image. Here, Miller and David E. Scherman take turns posing in Hitler’s bathtub in a staged invasion, which asserts a bodily victory over Nazi ideology as Miller and Jewish journalist Scherman wash away the clinging dirt of Dachau concentration camp — perhaps as fitting a symbolic retribution as one could hope for. The normalcy of the bathroom heightens the viewer’s horror over human evil, a theme Miller returns to throughout her war photography.

Lee Miller’s retrospective closes, perhaps surprisingly, with an optimistic second part to her collection: shots of collaborators and friends. After the rawness of her war photography and emphatic politics, the shift in tone could come as an anti-climactic end to an otherwise powerful exhibition. To some extent, it does. But mostly, it’s a touching conclusion to Miller as she was: an artist with a knack for connection. In a final shot flanking the exit door, she stands poised between mirrors on a tall ladder. Here, Miller is at the mercy of her own gaze as she becomes her own modelled actor — an infinite loop of observation fitting for a woman so at home in front of and behind the camera.

- WriterDaisy Finch

- Image CreditsLee Miller Archive