From the pit to the page: Bootsy Holler and the art of MAKiNG IT

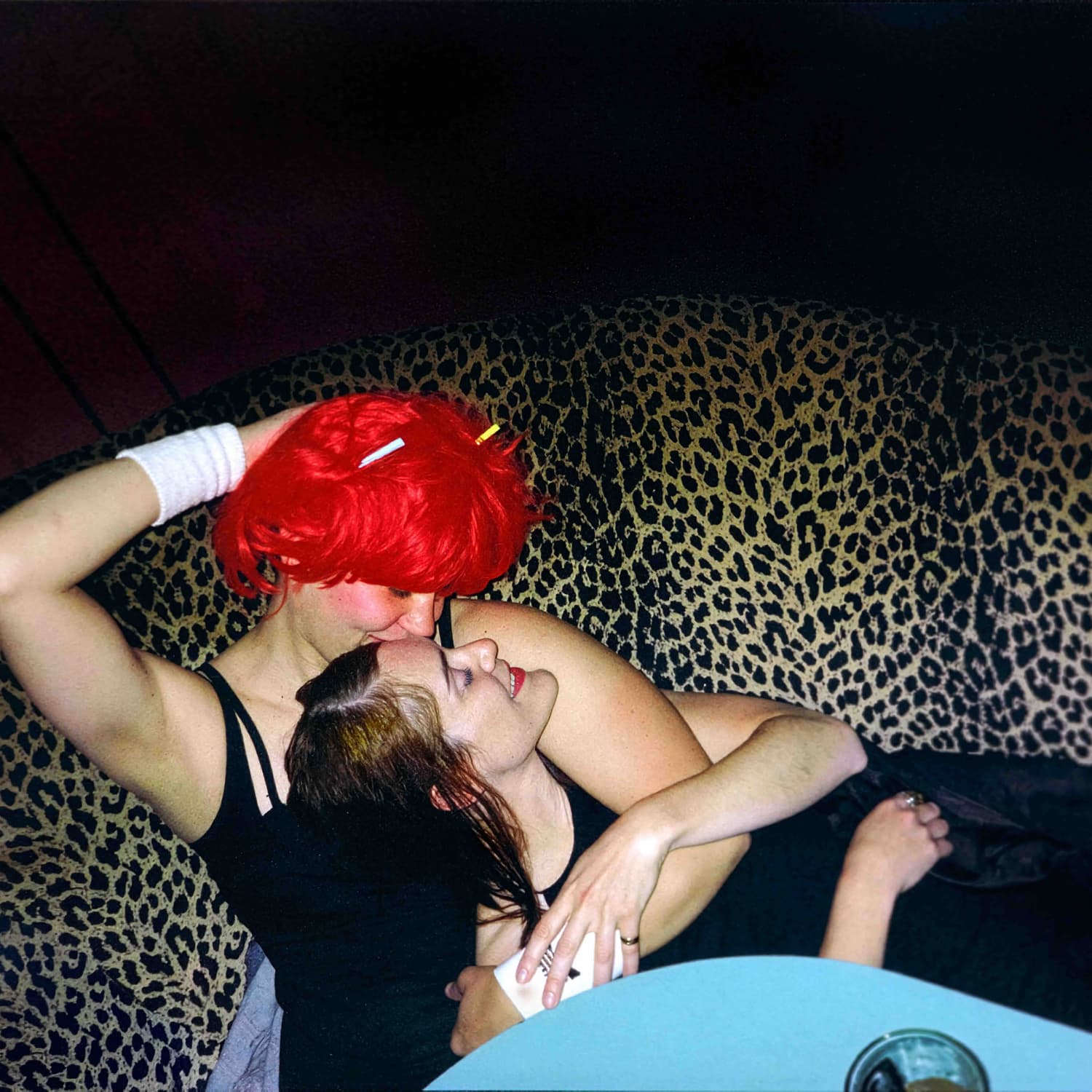

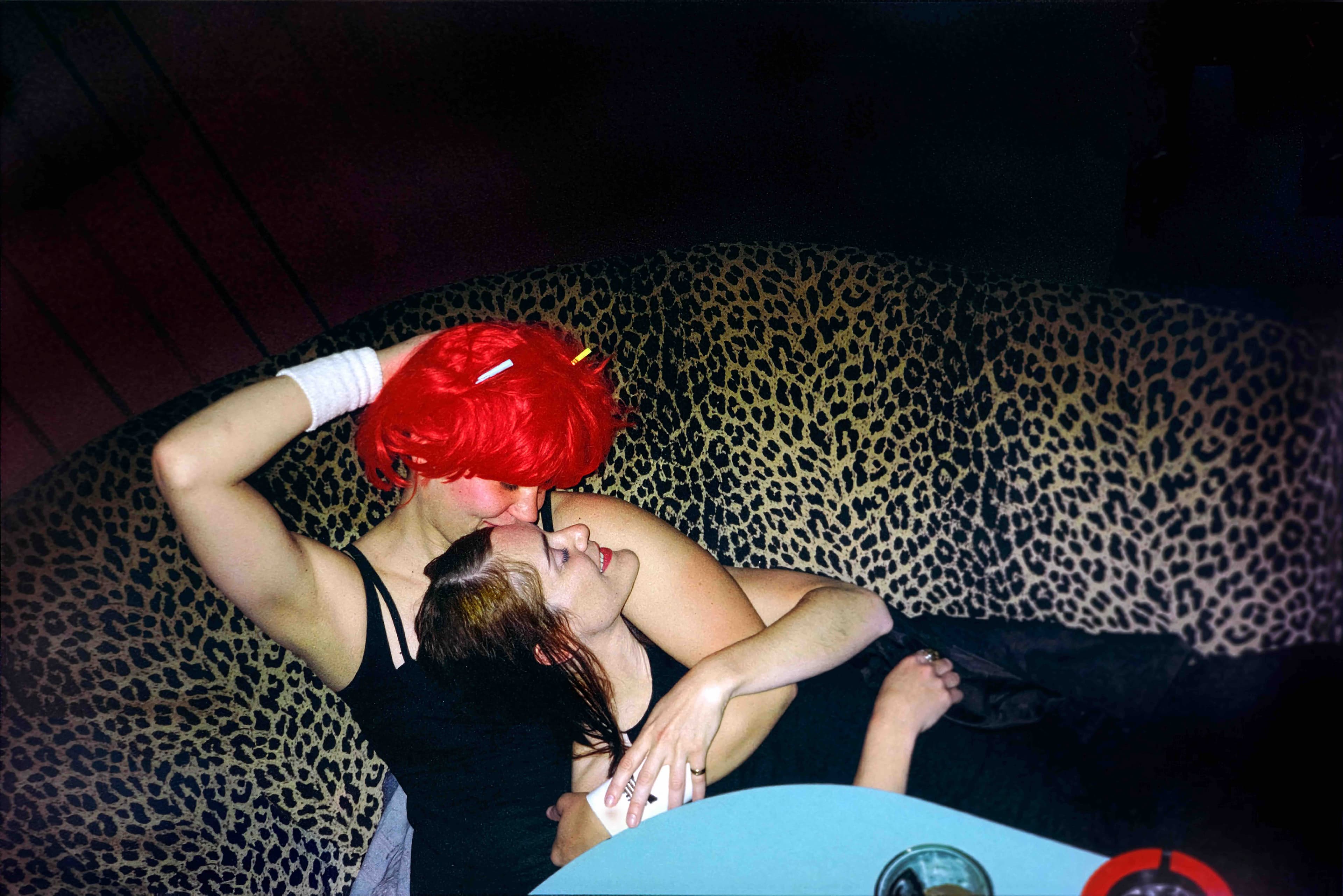

Each photograph in Bootsy Holler’s new book MAKiNG IT: An Intimate Documentary of the Seattle Indie, Rock & Punk Scene, 1992-2008 hums with a gritty mystique. A young band stands beneath the burn of venue lights. Sweat, static, the blur of a fleeting moment all thickened by cigarette haze in the frame. Their faces are charged with intent, but untouched by the burdens of fame. Between photographer and subject lies only the electric hum of idiosyncrasy.

There’s a tinge of ferocity to Holler. It’s strangely comforting in a way, resulting in my immediate embrace of her inspiring nature. Despite the laptop screen in the way — being on a Zoom call and whatnot — we hit it off immediately, nerding out about Pearl Jam and, on my part, how much of an honour it is to speak with someone responsible for an exclusive, never-before-seen photo dump, comprising some of the most loved bands from the noughties. These images capture a specific sliver of time: what Holler herself calls “a different kind of moment after grunge”. It was a world where Seattle’s pulse was electrified by a new wave of indie and rock bands that rose from the mundanity of the suburbs. Not a nepo baby in sight. That same energy, full of bite and individuality, is merely enhanced by Holler’s vision, resurrected in a visual love letter to the city’s restless buzz.

My first thought when opening the book was funnily enough Gil Junger’s 1999 flick, 10 Things I Hate About You, specifically Julia Stiles’ character, Kat Stratford, and her list of things she loves: “Thai food, feminist prose and angry girl music of the indie rock persuasion.” The page boasts vibrant pops of orange text, juxtaposed with black and white shots of an all-female AC/DC tribute band called Hell’s Belles, and oily saturated hues that encapsulate the decade’s comforting aura. Everything my London-native mind has ever imagined about Seattle was merely confirmed in the first three minutes of skimming through Holler’s photobiography.

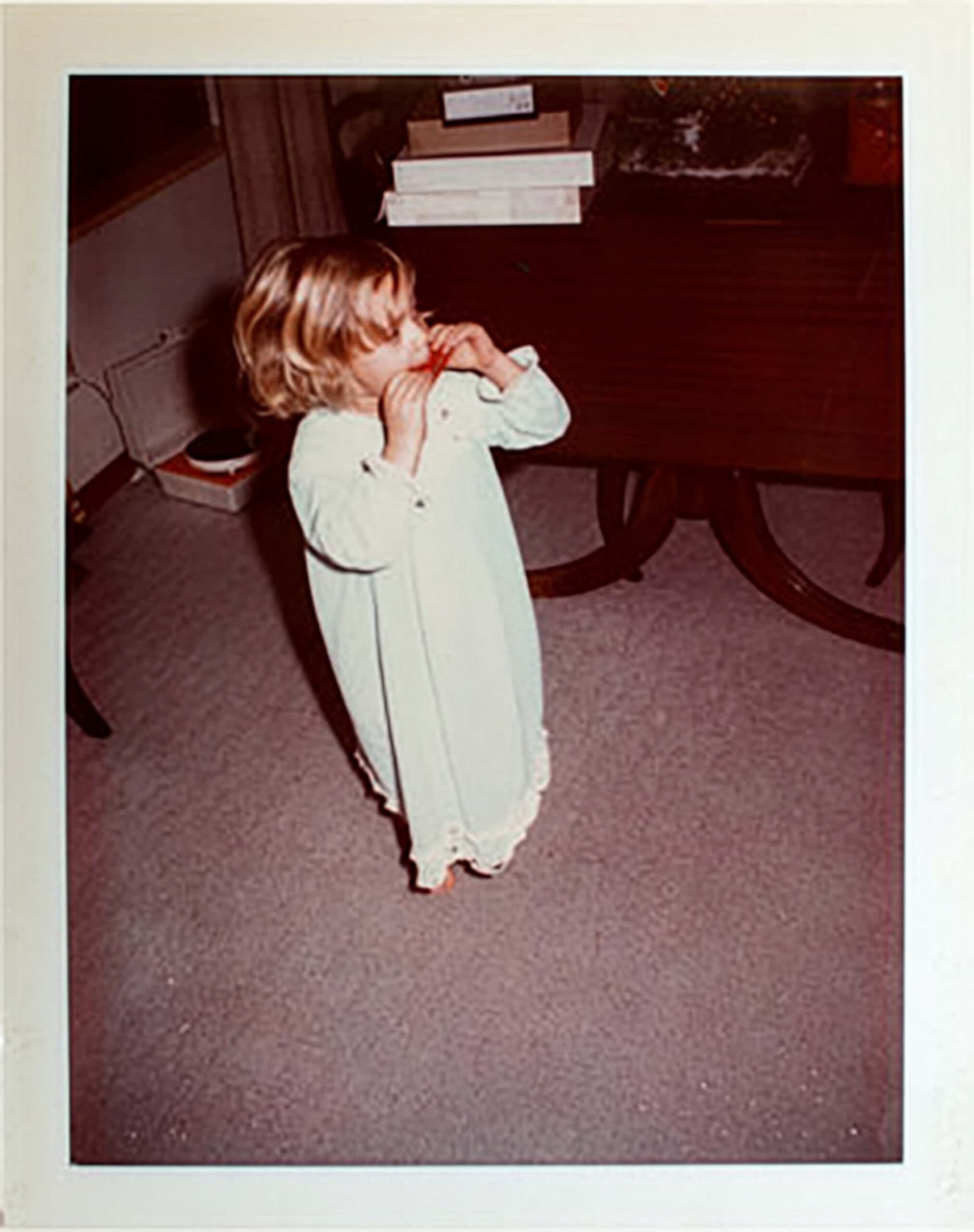

The title of the book may be incredibly long by usual photo book standards, but the word ‘intimate’ is true: it begins by reading like a personal diary, a scrapbook lost in the seams of girlhood. Photobooth strips of Holler herself are positioned on the left to immediately catch the eye — an ode to her first subject in photography. There are scattered concert tickets to PJ Harvey in 1992, Mazzy Star in 1994 and Radiohead in 1997, a worn-and-torn note with a handwritten ‘dear bootsy I love you’. It instantly brands the book as sentimental and special, regardless of the many photographic subjects waiting to be admired in the following pages. But most of all, it feels second nature to the music lovers consuming Holler’s art, as if we’re flipping through our own personal sentiments towards the artists we love and adore, and how relatable it is to feel the desire of ‘making it’.

Interestingly, though, when Holler began the book nearly ten years ago, it wasn’t for her. She had one simple intention: to leave behind something real for her sixteen-year-old son. “Before having him, I’d lived a very long,

crazy life on my own,” she says. “I wanted to document that time so he could see who I was before I was Mom.” Over that decade, the very process of scanning and restoring her negatives evolved dramatically, yet her vision held steady. According to Bootsy, making history was never her calling in life, yet this book proves she had answered that call without even realising it. Whether it’s a shot of young friends dining after a sweaty rock-out sesh, or of Lance Mercer from The Briefs completely dazed in his guitar-playing, it freezes an area in time just before everything changed — preserving the unfiltered humanity of a city mid-transformation.

The reader becomes the photographer, and each subject becomes a friendly face. “You can feel the energy coming through the book in all these people I shot,” Holler says. “But

I was there just fucking around, you know what I mean? I took my work seriously, but it wasn’t like it was a job. I wasn’t shooting for a magazine. I just knew exactly what I wanted to see.” What elevates each shot is the immediate responsiveness seen in Holler’s subjects, where each person — musician

or not — is enamoured by her vision, and thus embodies it. “That is definitely my art,” she tells me. “I can put people at ease, and my goal is to make you look good. I would never put anything out that I didn’t believe really showed that person in the best light, and that trust comes from who I am.” The photographer continues: “Being a woman, and asking a woman to do a portrait, that’s automatically a different trust right there. I have their back.”

That trust radiates through Holler’s earliest portraits, none more striking than her first formal shoot with Selene Vigil, lead vocalist of 7 Year Bitch. For it to be Holler’s first professional portrait, and to possess the confidence and grit it does, is a remarkable testament to her talent in subverting the control between two artists at opposing ends. For a split second, the volume of music collides with the volume of visual art, as one art form amplifies the other.

It’s now that Holler describes the generation of noughties creatives dedicated to outdoing their predecessors — one that I see present in her own art. “Because of the liquor laws in Washington State keeping out the all-ages kids, and grunge becoming hot, kids outside the city like Modest Mouse and Murder City Devils were outwardly against [what already existed],” she says. “They were rebelling against what was happening.” They were creating music that wasn’t the go-to grunge prevalent in Seattle, moving into a darker, more post-punk scene. That competitiveness, Holler tells me, brought all “this crazy energy into the city, where younger kids had different influences of music and came from all over into Seattle”.

That defiance bought a new kind of adrenaline into the city’s veins, bustling with constant energy for all types of artists. “It was a crazy time because of the birth of digital coming in. We’re seeing this resurgence now where kids want to shoot film, but back then, digital was so experimental. Nobody taught me Photoshop, nobody taught me how to use my Mac. It was just figuring it out, making it up,” Holler shares, give or take a few excited profanities. Her energy is magnetic. Soon I find myself dropping the F-bomb, too. “There was this weird experimental freedom in what you were doing, and it was a good age of not being afraid,” she continues. “It was about having more freedom, saying no to a nine-to- five job, and realising that you could actually make a living out of being creative.”

The improvisation was liberating and free of burden, but the creative high wasn’t always a friend. “When you were in Seattle, you were a snob of music,” Holler harks back. “The system of music was continuously flowing, and great bands like Pearl Jam had already gotten old to us in town. That blowing up of digital then gave everybody this newfound freedom, you know?”

This world, full of intimacy and interconnectedness, was one Bootsy embraced naturally. She wasn’t an outsider, looking in like her readers — she was part of the machine. “Back then, I was often the only person with a camera,” she says. “I’d hold it up at a venue, walk past the long line, catch the bouncer’s eye, and go in under his arm. I was part of the little family that ran the clubs, managed the bands, worked the door, and I really respected that.”

As a result, her photographs reveal a strong sense of humility, capturing moments like the late Chi Cheng of Deftones embracing Holler’s White Shepherd, Pony Girl. What might’ve been a simple portrait of a band becomes a fleeting reminder of mortality — a glimpse into the humanity within a scene built on constant noise.

That sensitivity underpins all of Holler’s work. “I hope the biggest takeaway from MAKiNG IT is that art is all about tapping into your heart,” she says. “Who you are when you create — even if it’s something really weird.” Here, Holler reiterates to me the same sentiment she shares in the book. “If it doesn’t feel right, move on,” she says. “There’s a shitload of stuff that didn’t get in the book, but you can only do so much.” That doesn’t mean she’s done, though. Holler tells me who she’d love to shoot one more time if she could. “I would love to shoot Wayne Coyne personally,” she says. “I have some shots of him, but I shot him in a tiny little fucking record store, and I didn’t even have a good camera. So a portrait of Wayne would probably be my biggest choice.”

In a time defined by overexposure, overconsumption and the development of social media feeds instead of negatives, MAKiNG IT stands as an insider’s glance

into a world before that — one full of interconnectedness and the embrace of originality. The book effortlessly positions the noughties as one of the greatest decades for music and art. Featuring trailblazers of the music scene like Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Nirvana, Soundgarden, and then those who add an element of surprise like Macklemore, Blink-182, Ice-T, No Doubt and Yeah Yeah Yeahs, the book is more than a photo-spread of Bootsy’s exceptional taste. It is talent, heavy experiences, compassion, individuality and the beauty of connection — all embellished with artistic detailing that evokes the captivating energy of a life once lived in Seattle.

Bootsy Holler’s MAKiNG IT: An Intimate Documentary of the Seattle Indie, Rock & Punk Scene, 1992-2008 is available now at select book stores and Primrose Hill Books.

- WriterIsha Khan

- Images courtesy of Damiani Books