Arty Appetite — Dirty Looks at the Barbican

“Are those the —?” “The Kate Moss wellington boots? Yeah, they are.” Sitting next to a pair worn by Queen Elizabeth II, (squeaky clean) wellies stand at the threshold of Dirty Looks at the Barbican, in a suitably irreverent introduction to the centre’s first fashion exhibition in eight years. While the wellingtons might be shining, Dirty Looks is host to enough decay, rust and dirt-stained drapery to keep visitors delighted and disgusted for hours on end. From its introduction, the exhibit is keen to establish ‘dirt’ as a high concept basis for a fashion show, citing Mary Douglas’ definition of dirtiness as simply “matter out of place”. Here begins our journey through the past half century of fashionable filth, where visitors can expect to rise up to the heavens before falling quickly back to earth, making their mark on the ground below and being marked in turn.

But first: to the skies. Subtle signs point visitors up a staircase and onto a circular mezzanine with an aerial view of the main space. Here, Hussein Chayalan’s ‘Future Archaeology’ dips elegant eveningwear in rust, the natural result of burying his garments, subtly dirtying them in a way that isn’t immediately obvious at first glance. Instead, sequins descend into large splodges of mud and orange. Earthy tones bury trembling beads. Its neighbour takes a more overt look at the socioeconomics of dirt — the so-called “nostalgia of mud” that plays between high and low culture. Coined by French playwright Émile Auger in 1855 (that’s some high culture for you), the term describes how people who live in the city long for a pastoral, rustic life. Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren borrowed the phrase for their 1982 Autumn/Winter collection, an example of which features in the room. But it’s the broader influence of this creeping nostalgia that the display focuses on, with examples ranging from Issey Miyake’s 1983 Spring/Summer collection to Pierre D’Angelo’s ‘Grow Your Own Couture’ built from sculpted faux moss with an earthworm bralette.

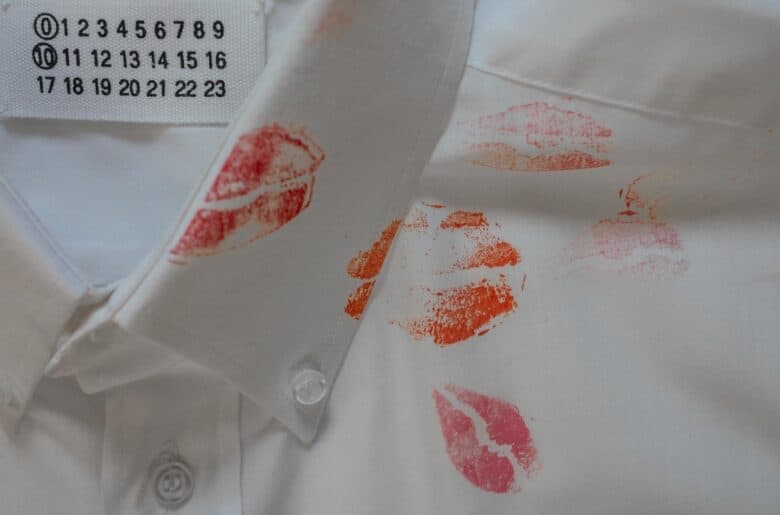

The true standout, however, comes about halfway through with the so-called “romantic ruins” of designers like Oliver Theyskens, Viktor&Rolf and Alexander McQueen. Viktor&Rolf’s 1993 ‘Hyères’ dress trickles grey scraps onto the step below its pedestal in a refreshing break from the otherwise sanitary walls — mess, if not dirt in its traditional form, has been allowed some room to play. True grubbiness in its joyful, confrontational, childlike state is most tangible in Leaky Bodies. The carefully curated pasta stains and red-kissed shirt collars that precede this are easily overshadowed by the period stains and sweat-drenched t-shirts. They’re no longer a matter of embarrassment, rather an unapologetic wink to camera on the inherently messy state of being human. When a Heathers-lookalike pops onto the screen in Michael Lucid’s 1996 short film Dirty Girls, crying out “You’re filthy! You’re filthy! I mean, God!” she is relegated to an outsider — it’s impossible to resist the frankness and charisma of the Nineties teens who visually embraced a ‘dirtier’ aesthetic.

If the upper floor sits in the sky, toying with the often aspirational, nostalgic connotations of ‘dirt’, the central exhibition space commands visitors to remain wholly in their bodies. Fleshy contorted fabric drapes across the walls. It’s not exactly dirty as I understand it, having recently scoured the London housing market, but it makes for a pleasant change from the white walls that cover the rest of the space. Instead, the regular drapes of these pink-hued curtains give the sense of being inside an intestinal tract after a very thorough irrigation. Issey Miyake’s Pleats Please, with an accompanying video on the Dragon Explosion that burnt through metres of fabric to pattern the dress, shows that decay doesn’t have to be a quiet, gradual thing, but can burn as hot as an open flame. Even sweat is given a glamorous makeover by Alice Potts in a piece commissioned by the gallery. In it, Potts has turned her own sweat and that of others into a purified mixture from which crystals start to grow.

Other highlights include Solitude Studios’ ‘After the Orgy’ in which bog bodies float like material ghosts and Michaela Start’s ‘Growing Pains’, which sees bodies transformed into and transforming the material that holds them. A triptych of white-washed walls sit to the side of this draped central display, noting the excesses and environmental impact of the fashion industry. The pieces and their minimalist sets confront the grimmer reality of fashion’s impact on the earth in a stark contrast to the previous world of bodily contortion and experimental design. It’s a sobering end to the explosive excess of filth that seeps through Dirty Looks, prompting visitors to consider whether we humans might be the dirtiest thing of all.

- WriterDaisy Finch

- Banner Image CreditJoseph Rigby courtesy of Paolo Carzana