What happens when the ‘Children of the 90s’ grow up?

Consider the following scenario: you’re enrolled in a vast scientific study before your own birth – and as such (inevitably) you did not consent to be a participant. Various samples (blood, saliva, urine) of yours are stored in a “biobank”, along with thousands of decades-old milk teeth and placentas; you’re encouraged and incentivised to be “monitored” throughout your life, including visits to a dedicated clinic – and any children you have will also be subjects of interest. Ultimately, you don’t know what exactly the data points and aggregated information you and the others involved provide will be used for in ten, even a hundred, years’ time.

London – alongside Beijing, Moscow and Baghdad – is frequently cited as one of the most extensively monitored cities in the world, one key metric being the concentration of security cameras per capita. No other European or American city breaches the top ten and China, Russia and Iraq are all countries whose governments we wouldn’t hesitate to label authoritarian. To put it another way: we’re in dubious company when it comes to our freedom and privacy.

Whether we think about it much or not, surveillance culture has become an intractable feature of contemporary life in the UK, particularly over the last two decades. We’re under constant observation, both on the streets of British cities and online, where tech giants – still flimsily regulated – deploy sophisticated algorithms that harvest our data and catalogue our behaviour, purchasing habits and ostensibly private interaction.

We’re being profiled, tracked and monitored in ways that simply weren’t possible in the twentieth century. And while it’s true that this sense of “being watched” – even in the seclusion of our own homes – provides fertile ground for the spread of conspiracy theories, most of us feel it in a more nebulous way. We tacitly accept that life in 2024 is characterised by a deep-seated distrust in institutions and authority and, frankly, we tend not to dwell on it. But while we may not pay much attention to this in our day-to-day lives, I suspect it contributes to a general sense of unease – bordering on paranoia – that affects us all as individuals. It may even be impacting the way we interact with one another.

Turn back the clock a few decades, though, and shift your focus to another British city: Bristol in the early ‘90s. Back then, a different kind of surveillance – much more benign but no less interesting – took a concrete form in a hugely ambitious study called The Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood (ALSPAC), known colloquially as “Children of the 90s” or “CO90s”.

What began as an experiment whose objective was to track the health and wellbeing of over fourteen-thousand pregnant women and their new-born babies – a “pregnancy cohort” – has morphed, over the last thirty years, into an unparalleled academic resource. The research project operates a biobank that’s currently home to 1.5 million biological samples, including “eight thousand placentas from the original pregnancies and over nine thousand milk teeth”. Growing up here, I’ve been aware of the study for most of my life in an ambient sense. But ignorant of its history and parameters, I spoke to Professor Kate Northstone, Executive Director of Data, who helped me understand its purpose, as well as the results it’s yielded.

“The original aim of the study was to see how the environment interacts with our genetics and affects children’s health”, she told me. Initially, the intention was to monitor the cohort up to the age of seven. But when the extent of the project’s potential became clear, it progressed and evolved – now encompassing three generations.

Last October, at an event dubbed “Discovery Day”, held at M Shed in Bristol, Professor Nic Timpson, Principal Investigator of the project, addressed a very particular and rarefied group of individuals: the subjects of the study. His speech was short, his tone warm and celebratory. Brimming with gratitude. But one particular remark he made stuck out to me: “There are literally hundreds of thousands of data points collected on you – you are the most deeply characterised pregnancy cohort in the world, and I can say that with absolute confidence.” It gestures towards the astonishing breadth and influence of the study but, somehow, it jars – the people Timpson was addressing are no longer a “pregnancy cohort” but adults now, all in their early thirties.

How does it feel, then, to be a member of this cohort? Monitored and tracked since before your own birth and the subject of a scientific study you were enrolled in – inevitably – without your consent? To put it bluntly: a data mine.

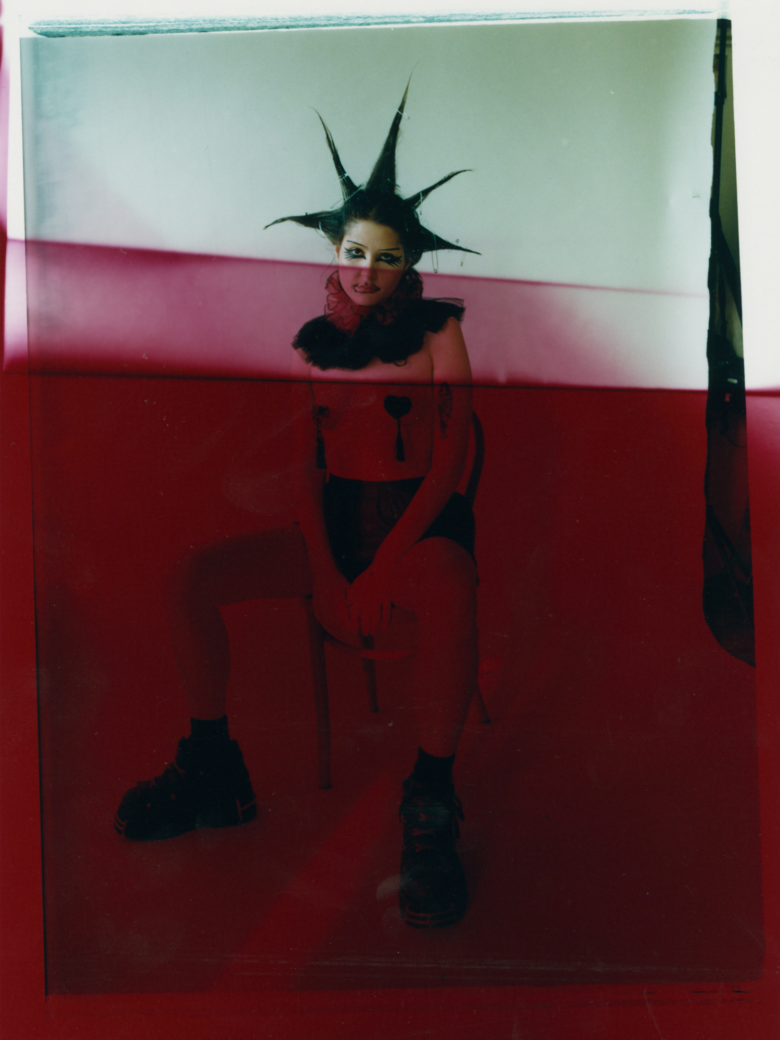

Will is thirty-two. On a Monday morning before Christmas we settle around the small kitchen table in my flat. It’s cold and he’s swaddled in a red speckled throw. Trim and composed, with blue eyes like pale crocuses and cropped brown hair that’s greying stylishly, there’s a calm but acute intelligence about him. I start by asking when he first became fully aware of his involvement in the study – and whether it marked him out from his siblings, friends and peer-group.

“I’m probably around ten years old – that’s when I begin to remember the visits to the clinic”, he tells me. And while he doesn’t recall much about those early episodes, he does remember “the little treats you’d get at the end… when you’re that age, they give you cute little gifts and you think, ‘that’s the coolest thing in the world’. I chose a silver holographic notebook”. He’s laughing as he tells me this, but “even small things like that – that you really care about when you’re that age – make you think, ‘this is quite special’. And, of course, you’d get to skip school that day.”

“Discovery Day” was a ceremony of sorts, marking three decades since the inception of this landmark study pioneered by Professor Jean Golding at the University of Bristol. To date, the research has been cited in over three thousand academic papers globally, with the data points, samples, and genetic materials collected from people like Will informing further research related to everything from the effects of excessive screen time on young children’s neurological development; the way our genes determine rates of obesity; the dramatic increase in liver disease diagnoses in younger demographics; and the prevalence of depression among women – both during and after pregnancy.

At its core, Children of the 90s is an ongoing assessment of its participants’ physical and mental health, “but with that comes a whole host of exposures which, in themselves, are important outcomes, and work together to affect the health, wellbeing and function of a population”, Professor Northstone told me. Its focus, paradoxically, is everything – and everyone.

Most significant in recent memory, is the role the research played in understanding the Covid-19 epidemic, as it began sweeping the nation in 2020. According to Timpson, “the pandemic brought home just how important measurement is – data, the capture of those data, and their interpretation and communication – and Children of the 90s has been at the heart of that”. The responses provided by participants to questionnaires they received throughout the pandemic, and over multiple lockdowns, directly informed the Government’s SAGE committee’s reports. Notably, these testimonies revealed that “the proportion of young people experiencing anxiety at the beginning of the pandemic [had] almost doubled”. This information was startling, if not surprising, and became a major talking point in the media.

On a wet Monday afternoon in early December, the rain unabating and relentless, the streets like urban marshes, I accompanied Will to his most recent visit to the clinic in Bristol dedicated to the project. The tests conducted by the nurse were fairly ordinary – the kind of examination you’d expect from a check-up with your GP – but they were much more comprehensive; the visit lasted a full three hours. Various samples were collected, including blood, saliva and urine – and a pamphlet I picked up at the clinic explained that “by storing and processing these samples, detailed genetic data can be obtained” which help inform researchers about the vital role our genes play in determining the likelihood of developing a host of diseases and ailments.

Many of the members of Will’s cohort now have children of their own, and this new generation is being examined in much the same way. But Will differs from most of his fellow participants: he’s gay and doesn’t want children. Does that set him apart?

He poses the question himself – “Is this where my involvement ends?” – but both his sexuality and his decision not to have children, at least for now, should be points of interest in themselves, he suggests. Regarding sexual orientation, and the extent to which it’s explored in the context of the research, he’s somewhat ambivalent. “What’s interesting to me is that it doesn’t seem to be a characteristic the clinicians are curious about. I don’t really remember being asked about sexuality or orientation.” Will adds a caveat here, though: “I remember once, on one of the teenage questionnaires, there was this one question, ‘do you feel any attraction towards boys?’”

As he continues speaking, just as tranquil as he was at the beginning of our conversation, he recounts a remarkable vignette. “It was a scary question because I was still so young, and it was the first time I was disclosing in an official way – even anonymously – that I was having those thoughts and feelings…” Will pauses briefly before summing up what must have been an unorthodox variation of the coming out narrative most gay people experience. “Before I’d even said anything aloud, I was indicating it on a questionnaire.”

I ask about mental health, too. But for Will this hasn’t felt especially relevant. “When it comes to looking at illness or mental health, that’s never really been applicable to me. I’m healthy… I think I’m the plainest, most vanilla member of the cohort. I’m ‘Mr Average’”. That’s how you feel? “Yeah, there’s nothing interesting to look at, specifically… the only thing that makes me different is that I’m gay – but that’s not something they seem particularly interested in.” More generally, though, Will’s enthusiasm for Children of the 90s is both clear and palpable; he describes his own involvement as a “privilege”.

“Because my mum took it so seriously”, he explains, “it reinforced that feeling… and I guess that’s why I’m so keen to keep participating. I feel a bit sorry for people who don’t feel that way”. This speaks to the rate of attrition Professor Northstone mentioned when I spoke to her, which is particularly significant among male participants. “Don’t you realise how great it is to be involved? You’re contributing towards something really important”, is how Will puts it. Children of the 90s is – in many ways – unique. Professor Golding, its architect and founder, created a biobank before the term even existed, and it remains an indispensable resource for academics worldwide. Just as Will recognises, ongoing participation is vital to the study’s long-term influence and utility – and having spoken to some of its custodians myself, I’ve seen first-hand how effusive they remain about its benefits – both historical and still unknown.

Given the concerns many of us harbour about surveillance, and the connotations that word is freighted with, it might seem strange for anybody to freely consent to their genetic material being gathered and stored in a biobank, unsure precisely of what it might be used for in the decades to come. But ongoing consent, and a fundamental trust – even faith – in the benefits of the project is key. Will’s own consent was sought and freely given a handful of times, even during that single appointment I was present for.

He could simply opt out and cease his involvement – and some do – but he’s chosen not to. Professor Northstone told me that while the study has, like any other large-scale research project of its kind, seen “a drop off in participation” attributable to various factors (like family and professional commitments or outdated contact details), they noticed a marked increase in engagement during the pandemic. And many of the original subjects, having lost contact with the CO90s researchers over the years, returned to the clinic for their “@30” assessments. She emphasised, too, that “the feedback we receive is extremely positive… it’s very rare that we’re made aware of participants having a negative experience”.

I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to say that we’re living at a time distinguished by a profound trust deficit. From (legitimate) concerns around our own overexposure to suspicion about what our personal data is used for by private companies and even governmental authorities.

The scientific method and, by extension, its medical practitioners, have hardly been impervious to this attitude. It’s probably truer to say that they have been some of its most high-profile casualties. The pandemic itself, and the vaccines quickly developed and rolled out to stem its spread, have been a preoccupation for credulous proponents of lurid conspiracy theories. The impulse to “question” – but really to traduce – feels especially febrile right now. And it’s against this cultural backdrop of cynicism and despondency that, admittedly, I initially found some of the language used by the academics overseeing Children of the 90s somewhat odd – almost sinister at times.

But hearing Will speak so candidly about his own experience, as well as speaking to Professor Northstone about the medical advances the study has helped bring about – and what she hopes it will go on to facilitate – have disabused me of any misgivings. The key to understanding the value and merits of Children of the 90s is to recognise that neither its methodology nor its objectives are remotely comparable to those of corporations like Meta, X (formerly Twitter), TikTok or Google – which I think we all have something of an uneasy relationship with.

While its purview is vast and often confoundingly complex, Children of the 90s is evidently a force for good. That’s clear from the way its influence has spread beyond a mid-sized English city, to the rest of the country and, eventually, many other countries too. Will’s cohort – a kind of micro-generation in itself – has helped accelerate the pace of scientific research in the realms of epidemiology, mental health awareness, genetic analysis and much, much more besides. New research projects, more granular in their focus, but only possible thanks to the huge amount of data gathered over more than thirty years, are already underway. This pioneering, dynamic and truly impactful scientific enterprise that’s constantly looking to the future is improving not just the lives of its immediate participants, but those of us all.