The people keeping London’s indie cinemas alive

For over a century, picturehouses have nurtured the love of moviegoers everywhere. As the zeitgeist has shifted and evolved, they’ve remained backbones of the global cultural milieu — a cornucopia of imagination, BO and awkward first dates. Amid the waft of flavoured popcorn and dirty socks, these institutions have offered confessionals, salvation and a pause in a world hurtling ever forward. They are the key to the back door of the wardrobe; the plunge down the rabbit hole into a realm left behind when childhood fades.

If cinemas are the key, then independent cinemas are the land itself, dedicated to preserving film in all its forms — old, new, foreign, or from within the Anglosphere — and to the joy of sharing it with others. Yet these sacred picturehouses now stand on the brink of vanishing. Since 2020, arts and culture spaces have steadily disappeared, replaced by high-rises and yet another chain coffee shop. Independent cinemas still bear the claw marks of Covid, made deeper by streaming services only a seven-day free trial away.

London, an epicentre of arts and culture, still boasts remarkable independents. The Prince Charles, Phoenix, Castle, Lexi and Rio are more than places to watch films; they are living cornerstones, sustained by passion from both their employees and their audiences.

Prince Charles Cinema, Leicester Square

Wedged in the guts of Chinatown resides the mothership of London’s indie cinemas. Its exterior, plastered with posters old and new, is flanked by clusters of patrons smoking, chatting, and dissecting the filmography of David Lynch. Above, a behemoth marquee displays ‘In the Mood for Love’s 25th anniversary’.

Inside, you’re hit with the lingering scent of popcorn and midnight movie marathons. The lobby buzzes; customers and staff chat warmly, as if old friends. This place is more than a cinema — it’s a place of worship and community.

At the heart of that community is Paul Vickery, the Head of Programming at The Prince Charles. After starting as a front-of-house employee seventeen years ago, today, he is the second-longest-serving member of staff. Vickery has helped craft the cinema’s famously eclectic programming, which he describes as an ongoing conversation with audiences — one that even prompted Paul Thomas Anderson to liken the venue to a favourite radio station, in that “there’s always something you want to see”.

Earlier this year, the cinema went public about the looming threat of closure after lengthy rental disputes with its landlord. Vickery compares the situation to “pushing a boulder up a mountain”, while also stressing that the fight to save the PCC reflects a wider struggle between cultural institutions and profit-driven property development. In response to the announcement, the ‘SAVE THE PCC’ petition was launched, amassing over one hundred thousand signatures in just one day — a testament to the cinema’s loyal audience and supporters.

Despite these challenges, Vickery remains optimistic: “We’re a single-site independent cinema going through the busiest period in our history. The majority of the audience are young, and that’s a sign of a culture that still loves going to the movies”.

Phoenix Cinema, East Finchley

In the heart of East Finchley’s residential high street, a white building sits embellished with a glowing red marquee. Today, it advertises Celine Song’s Materialists. On opening night in 1912, it was a film about the recent Titanic sinking. This Grade II listed building is one of the UK’s oldest, continuously-operating picturedromes.

Inside, there is a comforting sense of stepping into a bygone time — an age of cinema, bustling and groundbreaking. With historic barrel-vaulted ceilings and golden Art Deco panels, Phoenix Cinema, just like movies themselves, has gifted audiences with the opportunity to transport someplace else entirely.

Originally from Transylvania, Zalan Pall has spent four years as Front of House and Marketing Manager at Phoenix, following earlier stints at cinema chains like Everyman and Curzon. A lifelong cinephile — once attending over one hundred screenings a year — he trained as a projectionist before moving into management when digital cinema overtook 35mm. For Pall, the heart of independent cinemas lies in their ability to strike a balance between popular titles and more daring programming. Phoenix Cinema values showcasing underrepresented voices, young filmmakers and stories from overlooked regions.

Pall believes the personal touch sets independents apart from multiplexes, where it’s possible to have a cinema experience without interacting with anyone. At Phoenix, human connection is central to the experience. Pall warns that if independent cinemas were to disappear, cinema itself would risk becoming an elite pursuit, dominated by commercial tastes. “It wouldn’t just become too expensive,” he says, “but we’d be left with only the content the general audience wants to watch — so cartoonish that ultimately it would collapse. Art is about expression, and you can’t put a lid on it.”

Rio Cinema, Dalston

Shining its geometrically pleasing three-letter name over Kingsland High Street, Rio Cinema is Dalston’s crown jewel. A favourite among London cinephiles, it hosts premieres, Q&As and community events. The staff — tattooed, pierced and generous with popcorn — add to its charm. Inside, there’s a sense of camaraderie; an unspoken yet tangible understanding that you’re ‘in the know’.

Ror Brown, Creative & Marketing Manager at Rio, has spent nearly a decade shaping the Hackney cinema’s identity. Originally starting out in casual cinema jobs as a teenager, they worked their way up from front of house to duty manager and community coordinator. Their love for film began with Napoleon Dynamite in primary school — a quirky comedy that, beyond its quotable fun, revealed to Brown the power of intimate storytelling and self-acceptance.

For Brown, what makes the Rio special is its activist roots and ongoing relationship with its audience: it’s more than a cinema, it’s a community hub with a radical history, from hosting ‘Rock Against Racism’ gigs to pioneering female-led programming. Looking ahead, Rio stresses the importance of safeguarding spaces like this, warning that without independent cinemas, communities lose the chance to gather outside purely transactional spaces.

With its fiftieth anniversary as a community-run venue approaching in 2026, Rio Cinema plans to celebrate with archive projects, youth programming and memory workshops, all while keeping one eye on sustainability. “Maybe rooftop bees,” Brown jokes, “though worms and salty popcorn might not mix.”

The Castle Cinema, Homerton

Once upon a time, in a land far, far away (better known as Hackney), a castle for the people was built. For forty-five years, it served the subjects of east London with the latest pictures, from silent films to Hollywood’s Golden Age. Then, in 1958, the castle closed, reborn as a bingo hall, then a patchwork of businesses. Each year, its walls decayed, the spirit of cinema hiding in the cracks. Until 2016, when a Kickstarter and six hundred and fifty donors saved the castle and restored its true form. Today, The Castle is a beloved staple of Homerton and its surrounding kingdoms.

For the past two years, Corinne O’Sullivan has been The Castle’s reigning general manager, bringing with her a background in live arts venue management and experience at Rich Mix in Shoreditch, where she first caught the “cinema bug”. Having lived locally for five years, she jumped at the chance to lead her neighbourhood cinema.

Though loved and visited by many, The Castle is no stranger to the current cost-of-living crisis. With the task of balancing affordability and sustainability becoming increasingly difficult, the small, close-knit team have found creative solutions, spanning ‘Supporter’ tickets to £6 Monday screenings. Programming, O’Sullivan says, is its own game of Tetris, a constant effort to align blockbuster demand with the responsibility of spotlighting smaller films. But the “magic of the movies” and community vision that crowdfunded The Castle into existence back in 2016 are what sustain her.

Looking ahead, O’Sullivan hopes the cinema continues to serve as a cultural hub, a place woven into the rhythms of daily life where audiences recall not just the films they saw, but the fact that they experienced them at The Castle.

The Lexi Cinema, Kensal Rise

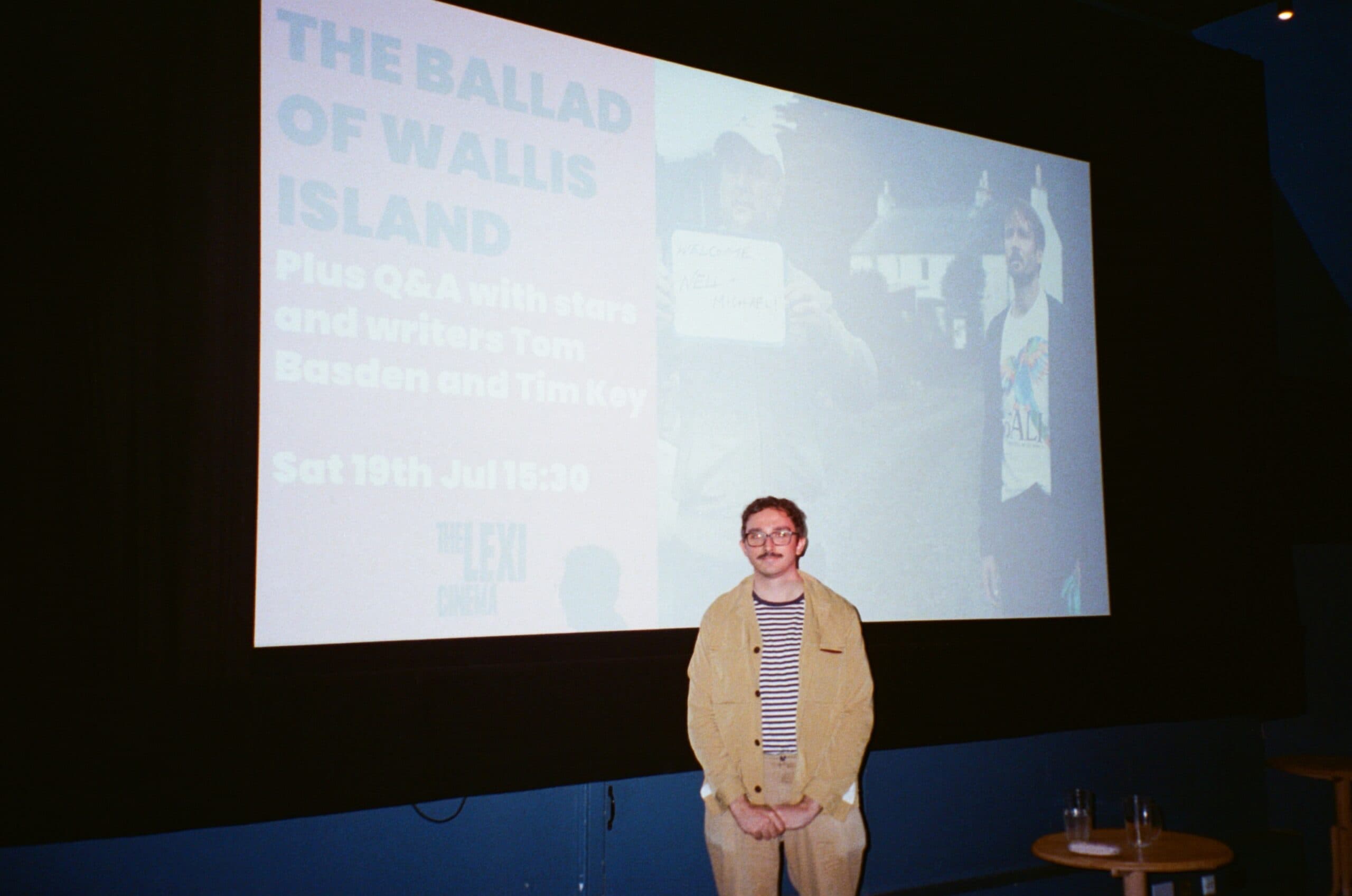

Nestled in the quaint north-west neighbourhood of Kensal Rise, The Lexi is London’s only social enterprise cinema: a boutique, two-screen picturehouse for the people, by the people. What makes this place unique is that it’s mostly volunteer-run. When you’re greeted, you can be assured it’s by someone who cares about both film and the future of independent cinema.

Earlier this year, before the Oscars, The Lexi was one of the few London cinemas screening the Palestinian documentary, No Other Land. If that doesn’t tell you what kind of place this is, nothing will. The Lexi is more than a cinema — it’s the beating heart of social causes and underrepresented voices.

At the helm of The Lexi is Co-Director Johnathan Kirk. After six years working in cinema, beginning in marketing at The Ritzy, Kirk has found his place here in a role that allows him to focus on the part of the industry he’s most passionate about: programming. At The Lexi, decisions aren’t solely dictated by box office expectations, but by curatorial instinct and community connection, with audiences trusting the team to champion films that deserve attention. Though the cinema’s core demographic tends to be older, screenings of classics often draw younger crowds, illustrating its reach across generations.

Founded in 2008, The Lexi was established as both a cinema and a community hub, with its proceeds supporting the Sustainability Institute in South Africa after a tornado damaged the local area. One of its most meaningful projects, the Women’s Refugee Film Club, offers monthly screenings and discussions for refugee women and children in partnership with Salusbury World, fostering connection and joy through film.

For Kirk, initiatives like this highlight the irreplaceable role of independent cinemas as community anchors, offering spaces and experiences multiplexes cannot. While he admits the industry’s future can feel uncertain during quieter periods, the passion of younger audiences for older films gives him confidence that cinema’s unique power to inspire will endure.

- Writer and PhotographerAbi Turner