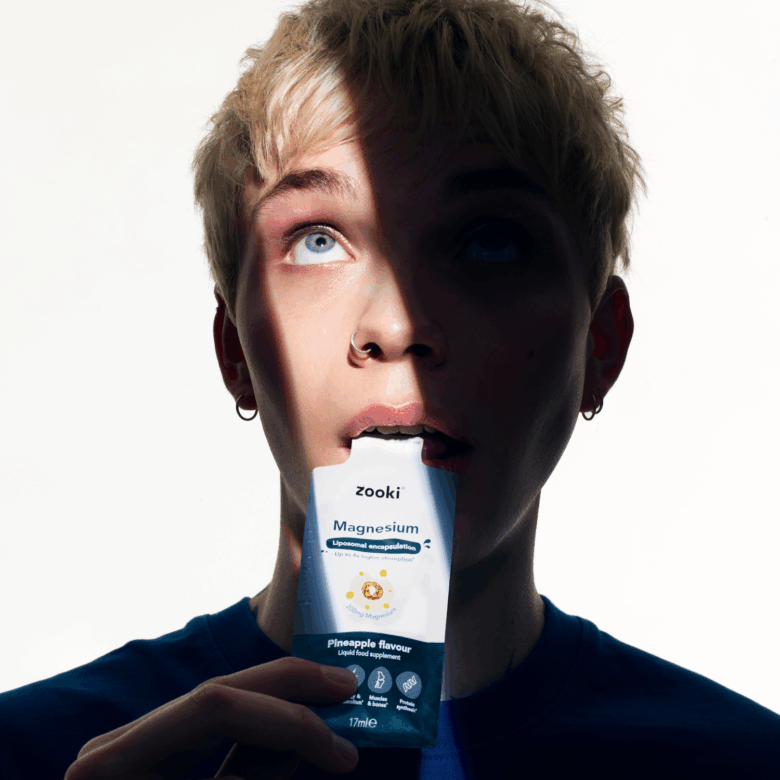

Tahar Rahim is sparring with his best self

When Tahar Rahim opened the script of his latest film, Alpha, one thing was immediately apparent. “When you read the script, you knew that you had to be very thin — that it would be an ordeal. It was inherent to the project,” he says. As an actor, Rahim has long been known for his physicality. When he speaks of his characters, he talks of having to go through their bodies to get into the heads. But, even for him, the transformation into Amine, a character struggling with addiction, would be dramatic. Rahim was already lithe, with a frame that felt powerful in its functionality. So when he lost just over three stone, he was unrecognisable. “If I don’t do this, I ruin the movie from the inside out, Rahim recalls. “It wasn’t even a conversation.” It did become one, though. As Rahim grew thinner, Alpha’s director, the visionary French auteur Julia Ducournau, sat him down and immediately expressed her concern. “She said, That’s enough,” he recalls, a smile slowly widening across his face. “And I said, I need to go further.”

Throughout his career, Rahim has constantly pushed himself to go further. On screen, he’s known for playing men with complex interior lives — ones that are sensed hovering just under the surface but never quite see the light. His diligence precedes him. He’s renowned for always asking for one more take and for his commitment to realism. When he starred in The Mauritanian as Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a man wrongly accused of terrorism and imprisoned in Guantanamo Bay, he was offered fake shackles by production. Rahim refused, asked for real ones and carried the bruises on his wrists for the next two weeks. There’s an intensity with which Rahim approaches his work — this is his job and he treats it as such — but it doesn’t bleed into existential self-seriousness. In person, Rahim is immensely affable, charming and speaks in a transatlantic accent that gives an air of Old Hollywood.

On set, though, Rahim’s pursuit of realism is a way of bringing him into communion with what his characters would have truly experienced. Losing weight to play Amine wasn’t just about looking correct, but feeling correct, too. “Physically you move differently,” the actor explains. “You don’t walk the same way, jump the same way, lay down the same way. You’re sort of a different person. Still you, but different. What the camera catches is the truth.” It not only looked real on screen, but Rahim felt the effects of deprivation in real life. On longer shoot days, he found himself barely able to stand and yet found no relief sitting. There was so little fat left on his body, even that was painful. While the weight loss took a toll physically, Rahim also noticed changes to his mental state. “You get weaker but somehow it opens a window that you’ve never expected,” he says.

As his body existed in a state of deprivation, Rahim’s emotional state clarified. “I felt like I was more spiritual, more connected to something else — to others, to God,” Rahim remembers. “I’m a believer and I pray. Sometimes the prayers get a little mechanical, but on this diet, I felt laser focused. Everything was crystal clear. There’s a reason why every important prophet in every religion had a moment of isolation and fasting.” Like those prophets, Rahim filmed Alpha in isolation — specifically in Le Havre, a city on France’s northern coast, roughly two and a half hours away from his family in Paris. Throughout production, Rahim stayed in a room with an ocean view. His diet was devoid of all pleasures — except the occasional handful of cherry tomatoes and pistachios — and as he sat with this restriction, he began to feel more deeply in tune with the world around him. “It’s a little odd to say — and I’m not crazy — but I was right in front of the ocean and I could feel the water. I felt like I was really talking to God. I could feel the creation.”

What grounded Rahim through this challenging journey was his relationship with his director, Ducournau. Although the pair had never previously worked together, from the moment they met, it felt like kismet. “I had a gut feeling that it was going to be right. And I mean, spot on,” he recalls. “I don’t know how to explain it, but it felt like we knew each other.” Although the first impression felt fated, Rahim was cautious, knowing that you only truly find out who a director is on the first day of filming. But when it came about, everything locked into place. “We started the first sequence, first scene, first take — it clicked.” Although Rahim still can’t quite articulate what makes their relationship so special, he does understand what it gave him — the permission to try. “The best gift a director can give you is a sort of freedom,” he states. “It’s a perspective — that you are surveilled, somehow, but free.”

The actor has made a career of working with great directors. At twenty-eight, he landed his first major role in Jacques Audiard’s A Prophet as an illiterate teenager thrust into the prison system. His performance drew widespread acclaim, winning him the César Award for Best Actor and leading him to be dubbed the ‘French Al Pacino’. In the wake of the film, eyes began to turn to what Rahim would do next. Journalists and critics proclaimed that he was destined for greatness and Hollywood called, but Rahim didn’t answer. “In Hollywood I had an agent, but they would just offer me terrorist shit — and I was never going to do it,” he remembers. “Hollywood, yes, but not at any price.” Within France, the situation was equally as bleak. “I didn’t feel represented,” the actor tells me. “When I would watch French movies and see minorities, they would always be represented in very small parts — robbers or rappers or snitches — but they weren’t proper characters.”

This cinematic reflection didn’t align with Rahim’s reality. The actor was born in Belfort, a small city near the French-Swiss border, where he lived with his parents and nine siblings in a fifteen-storey tower block. “I was raised with many different people from different cultures. I couldn’t buy a flight ticket so I’d push the button on my elevator and I would travel to Africa, Asia, North Africa,” he recalls. “I’d listen to different languages, taste different food, listen to different music. That was my way of travelling. It built the man as well as the actor, somehow.” As Rahim compared the vitality of community with its depthless portrayal in French cinema, he also considered his own standing. “The French directors would look at me from the inside. Foreign directors looked at me differently, from the outside. And surprisingly they would see me better — and they’d give me better parts.”

And so, in much the same way that Rahim travelled in his elevator, he began to travel cinematically. For the best part of the next decade, he worked with visionary filmmakers from around the world: Asghar Farhadi, the Iranian master of the kitchen sink drama; Fatih Akin, the German-Turkish chronicler of visceral urban life; Lou Ye, the sensual Chinese sixth-generation filmmaker who faces censorship in his homeland. “It doesn’t matter how much you travel, when you work with an important director, they’ll give you an insight from a perspective that you will never have, because they’ve spent their whole life studying their own culture so that they can tell it to the world,” Rahim says, before he bursts into laughter. “Having a conversation with a director, it’s even better than a tour bus.”

Few, if any, actors could say that they’ve worked with as many legendary directors as Rahim, and he holds this honour close. “I don’t want to disrespect the privilege I have to be an actor,” he says. Each of the filmmakers that Rahim has worked with has taught him something – and every great director has shown him that what he thought was impossible can be possible. As he approaches his third decade in the industry, Rahim is steadfast on one thing — continuing to experiment. “I think I’m running after one thing, the most beautiful thing ever, and that’s ‘the first time’,” he says. “Because the first time happens only once, you can only chase it by taking risks.”

And ultimately, Rahim’s whole career can be seen as an act of risk taking — making decisions that skirted Hollywood, waiting until the time was right, seeking out the creation of great art. In doing so, the actor has constructed a truly unique body of work, and cemented his position as one of the all-time greats. “I want to try and reach the highest level of this experiment in this art,” he concludes. “I see it just like a sport — boxing — but my sparring partner is the best version of myself.” Rahim pauses. “I know that I’m never going to win, but I could give one or two good punches back.”

This story was taken from Issue 37: Here We Go Again.

- PhotographerRankin

- Fashion DirectorMarco Antonio

- WriterRob Corsini

- Groomer Charlie Cullen at Forward Artists using ERBORIAN

- All clothing, shoes and accessories throughout LOUIS VUITTON SS26 Pre-collection