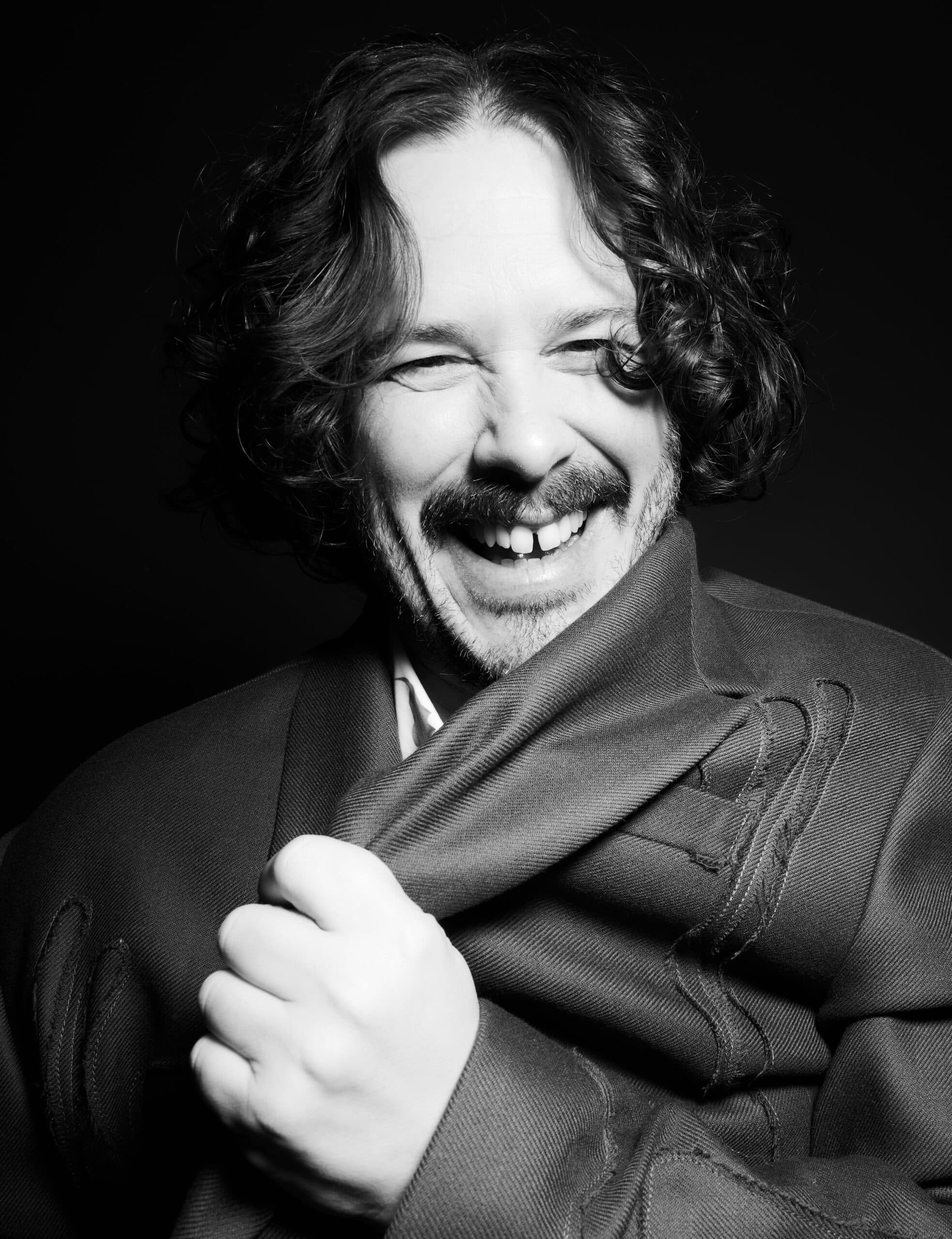

Edgar Wright really, really loves films

When Edgar Wright joins our Zoom call on a customarily chilly October morning, his first words come with a charming prelude: he’s ordered a coffee, which should be arriving any minute now. Should he have to dash to get it mid-conversation, he asks for my patience. It’s a perfectly Wrightian entrance — casual, human and with just a hint of impending urgency. For those unfamiliar with the British director’s work, it’s a fitting microcosm of his creative universe: a pulse of sharp wit, a rhythm that never quite settles and a suddenness that keeps you on your toes. Sure enough, just as he begins to unravel a thought, his coffee is ready. Back on screen moments later, Wright settles into that space between director and raconteur, a man whose life seems to be lived in cuts, beats and frames. His words come measured and deliberate, every pause a clip in an unseen edit. There’s warmth behind the precision — an easy charm that draws you in, like a favourite film you never tire of returning to. If there’s one thing immediately clear, it’s this: Edgar Wright is utterly, unabashedly and irrevocably in love with movies.

This affection is contagious. Over the course of our almost hour-long conversation, Wright’s thoughts sparkle with references, a rapid-fire catalogue of filmmakers and cinematic revelations. “I haven’t actually seen that many movies this year,” he confesses when asked about his recent favourites. But then, after taking a moment to reflect, he unleashes a torrent of titles and directors with unabashed enthusiasm: Park Chan-wook’s long-awaited No Other Choice, Harry Lighton’s directorial debut Pillion, Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague, Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another; among many others, each title an example of his deep devotion to the art of filmmaking. Even when discussing the nuts and bolts of his craft — Texas switches, choreography, lighting, inspirations — there’s a palpable boyishness lurking beneath, the echoes of the kid in the South West of England who spent days and nights making short films with a Super 8 camera gifted to him by a family member.

Today, however, the focus is on The Running Man — Wright’s first feature in four years, his inaugural Stephen King adaptation and, by his own measure, the most ambitious project he’s ever undertaken. Set in a near-future dystopia where reality television and bloodsport collide, The Running Man is a propulsive action thriller following Ben Richards (Glen Powell), a working-class man who enters a deadly game show to save his daughter — only to become an unexpected symbol of defiance in a society addicted to spectacle. “It’s a real gift,” he says, reflecting on the opportunity to adapt one of the first Stephen King books he read. “I’m genuinely so proud to have had the opportunity.” This pride isn’t mere vanity from having adapted a King novel. It’s the hunger to inject his signature rhythmic precision and human detail into a narrative charged with spectacle, survival and the merciless gaze of a watching world — one penned by an author whose work Wright grew up with.

The director explains that his relationship with King’s work dates back to his early teens. “He was one of the first ‘grown-up authors’ I’d read,” he recalls. The Bachman Books — a collection of short Stephen King novels, including The Running Man, published under the pseudonym Richard Bachman — were, for Wright, an initiation into the terrain of grittier storytelling. But the driving force behind this adaptation was not mere nostalgia. It was a yearning to revisit the story with fresh eyes and offer a vision closer to King’s original text than the iconic but decidedly 1980s film adaptation starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, which strayed from King’s book (to the author’s chagrin). “The idea that there was a different adaptation waiting to be made of that book always stuck with me,” he reflects. “One that was maybe a little more faithful.”

So, the scriptwriting process was a blend of excitement and pressure. For years, Wright had exchanged emails with King — mostly about rock music. The director’s encyclopedic taste in obscure albums had sparked a musical camaraderie with the author. But when Wright’s screenplay, co-written with Michael Bacall, finally reached King’s inbox, the thrill morphed into anxiety. “I was terrified,” Wright admits, recalling how he had been working on the script for at least two years before sharing it with the author whose writing, it would not be an exaggeration to say, has inspired hundreds of films. King pored over the script, reviewing it page by page — but by the fifth, he was completely sold, firing off an email brimming with enthusiasm to Wright. Relief. It was a “blessing and a curse,” the Dorset-born director explains: the blessing being that King loved the script; the curse that “we still have to make the fucking thing”. But when King finally saw the completed film and declared his approval, contentment washed over Wright.

Filmmaking, for the director of the beloved Cornetto trilogy, is a relentless pursuit of an ever-elusive ideal: the moment when every element clicks, when rhythm, performance and image coalesce into something transcendent. His obsession with timing is near-mythical, a signature that threads through his entire body of work — be it the razor-sharp opening montages of Hot Fuzz, or the perfervidly choreographed bursts of sound and colour in Scott Pilgrim vs. The World. And bringing that to life is exhausting. “It’s been a year of six and seven day weeks,” he says of working on The Running Man. “I had thirty days straight with no day off at one point. But I’m proud of what we pulled off.” That weariness is there, but so is a fierce satisfaction. It’s a devotion that pulses through every frame he crafts. Making movies remains, in Wright’s words, “a mad scramble to do more with less”. And that challenge, that tightrope walk between ambition and limitation, is part of the thrill that keeps him motivated.

Perhaps surprisingly for some, the same director known for kinetic, rapid-fire editing is also captivated by the opposite challenge: slowing down. To linger. To hold a frame in space and time and let it breathe. To keep toiling, striving to find the perfect shot. “The day you say ‘that’ll do’ and move on, even when you don’t think you’ve got it, that’s the day it’s over,” he says with quiet conviction. Wright’s films may feel effortless, even casual at times, but they are the product of painstaking craft. From the fastidious choreography of Shaun of the Dead’s iconic long takes to the blistering getaway sequences in Baby Driver to the dreamlike nostalgia woven through Last Night in Soho, Wright’s precision creates a unique kind of cinematic pulse. The Running Man promises more of that meticulous magic. He lights up as he describes one particular sequence: a traffic-jam shot filmed as the sun was setting. “The last take before we lost the light is the one that’s in the movie,” he jubilates, crediting cinematographer Chung-hoon Chung for making it look “so incredible”. That attention to detail, I realise, is what defines the filmmaker.

But, far from the creative stereotype — even in spite of the director’s rising fame and a growing body of acclaimed work — humility remains a cornerstone of Wright’s identity. “I never want to stop being the audience member,” he says. It’s easy to imagine a director, after years in the spotlight, growing jaded or distant. But Wright’s appetite for discovery remains insatiable. Even as his films become blockbuster events, he still craves the raw thrill of watching a movie as a fan. “I’ve seen people who, once they reach a certain level, stop going to the cinema with the public,” he notes. “I never want that. I still go — whether that’s to sit in a packed house or a half-empty matinee.” He’s got a secret Letterboxd account, too, though he prefers to keep track of the films he’s seen the good old-fashioned way: the Notes app.

The director continues and my hunch about him is confirmed — he is a man whose curiosity extends beyond the frame, driven by a fascination with the world that shapes the stories he tells. When I mention I’m from Pakistan, Wright is inquisitive. “I’d love to go. It’s a country I’ve never had a chance to visit,” he says earnestly, the spontaneity of the moment a reminder that, beneath the success, lies a man wide-eyed and eager to expand his horizons. It’s also that very spirit that drives his much-loved annual playlist of his favourite songs of the year — though he tells me that he sometimes thinks about stopping them “because I don’t want to ever be the sort of fifty-something who’s trying to be down with the kids”. I tell him to keep them coming — we all love them.

As our conversation draws to a close, Wright paints a final image. His perfect day off after months of relentless prep, shooting and post-production is walking down to the BFI or a local cinema and watching a classic, or two, or three on the big screen. It’s a simple pleasure, and yet one that also feels poetic. The boy from Somerset with a Super 8 camera who loved nothing more than movies, and the auteur orchestrating kinetic explosions of colour and sound are threads of the same fabric. The director and the cinephile are inseparable. Wright wants to keep sitting in the dark and be inspired by other filmmakers’ frames, even as he builds his own frames to shape others. The Running Man is, in many ways, the embodiment of this philosophy: a film forged by someone who still loves to be surprised, who still sees beauty and danger in every shot. For Edgar Wright, every cut, every long take, every risk is part of an ongoing quest — one of retaining, sharing and inspiring the magic of cinema. And as ever, he’ll keep running on what’s most important: an enduring love for storytelling.

The Running Man will be released 12 November 2025.

- PhotographerRankin

- WriterHamza Shehryar

- ProducerShania Yasmin

- StylistLewis Stratton

- GroomerJoe Mills at Joe Mills Agency using DIOR Beauty, Circa 1970 Beauty, Kevin Murphy and Woolf Kings

- Photo AssistantCharlie Cummings

- Fashion AssistantsLouis Sahota, Zoë Thabile

- Groomer AssistantMilo Mills at Joe Mills Agency