Why I invited a would-be terrorist into my home

I was only 13 when we fled my childhood home in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, 18 miles north of the capital, and trekked the mountains with just the clothes on our backs to find safety in a Pakistani refugee camp. My father and eight-months-pregnant mother, and my brothers and sisters – we all risked our lives to avoid the Soviet invasion of our homeland.

My father was a respected man in our village, a community doctor. I was blessed to be born into a family like mine and I saw from a young age what it meant to help people and how much someone can take from it. After six years in the refugee camp, I got engaged to my fiancé, Saber. He got a passage to the US as a trainee doctor, so I got a US visa too and joined him in Muncie, Indiana, in 1986. As soon as I landed we got married and we went on to have six children – three boys and three girls. But it took another 12 years to get my parents and my mother-in-law with us. It was a long, arduous process, but worth it in the end.

I’m the kind of person who, when a community invests in you, I like to invest back. The city of Muncie has been kind to us since we arrived, so it’s now more of a home to me than my birth country. People called the US a melting pot, and we personally experienced no animosity. When my husband and I opened our Islamic centre, there were objections from a few neighbours who didn’t want us to build anything from scratch, so eventually, we bought a building and remodelled it into an Islamic centre instead.

One day in 2009, my husband came home and told me about a man, US Marine Richard “Mac” McKinney, who had come into the centre looking lost. My husband felt something was wrong, and true to our faith and my husband’s personality, he went over to him and welcomed him with a hug. The next day Mac came back. I was in the centre and I talked to him, and this went on. We heard other people’s concerns about Mac’s motives. Many stopped going to the centre. But my husband and I continued – it’s who we are, we’ve always taken care of people who are sick or living with trauma.

However, it transpired that Mac did have an ulterior motive the day he first entered our mosque. He had been heavily affected by his 25 years in the military fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan and Iraq. He had been trained to see people he was killing as paper targets. Mac hated Muslims. He had intended to bomb our mosque and was hoping for at least 200 dead or injured on a Friday afternoon when we have our Friday prayers.

I refused to be deterred. I believe those who have struggles need our help more than anyone. I know many people would have walked away, but I am different. So I made a decision and I invited Mac and those people from the mosque who were scared of him to our family home for dinner. I cooked a typical Afghan meal and Mac finished the lot – he loved it. At the end of the evening I sat next to him and told him what we had heard and asked him directly if it was true. He explained his feelings, the post-traumatic stress from his days fighting the Taliban and his inner anger and voices. He was a broken man and he needed our help. Mac slowly healed and even converted to Islam. He became a respected man and served two years as president of the Islamic Center of Muncie.

Then the Jewish filmmaker Joshua Seftel approached me about a documentary. He had been working towards combating Islamophobia and religious-based hatred after growing up around discrimination as a Jew in New York and wanted to do a film on our friendship with Mac. I wasn’t sure I wanted to be involved at first. After 9/11 I stopped watching TV. I just couldn’t bear the negativity and hatred. I was happy getting my message across through my work, running my nonprofit organisation, AWAKEN – Afghan Women’s and Kids’ Education and Necessities – which helps those in Afghanistan. I also volunteer at a local women’s shelter, the YWCA, Muncie Rotary Club and the Interfaith Fellowship, while serving on local boards.

I like to help people and, in August 2021, when the US government pulled all troops out of Afghanistan, it broke the country and I had to step in. I still have brothers and sisters living in Afghanistan, and nieces and nephews. They were devastated when the schools closed for girls. In the past year, more than 400 private schools have had to close, according to educators. And, per the UN, suicides among girls and women have increased, as have mortality rates, including maternal mortality. Overall economic losses to the country due to the erosion of women’s employment are estimated at up to $1 billion. Boys are fleeing by foot, hoping to reach other countries, but reports say that some are being kidnapped and killed on the way. Many girls are staying at home, too afraid to leave. It’s devastating. But through my nonprofit group we managed to help 127 people, 37 families, resettle here in Muncie. I feel the city of Muncie is shining, which has always been my mission.

I tell anyone going through hard times that there will be a better tomorrow and try to empower them in any way I can. I think it’s one of the reasons I eventually agreed to be part of the [Stranger at the Gate] documentary. I had always considered writing a book and now I had an opportunity to get my message out there. I’m so proud of it. At screenings, I’ve had young Muslim and other people from minority backgrounds come up to me to thank and hug me. All we can do is do better for our humanity, collectively.

Stranger at the Gate is available to watch on newyorker.com. To learn more about Bahrami’s work in Afghanistan and to make a donation, visit awakeninc.org

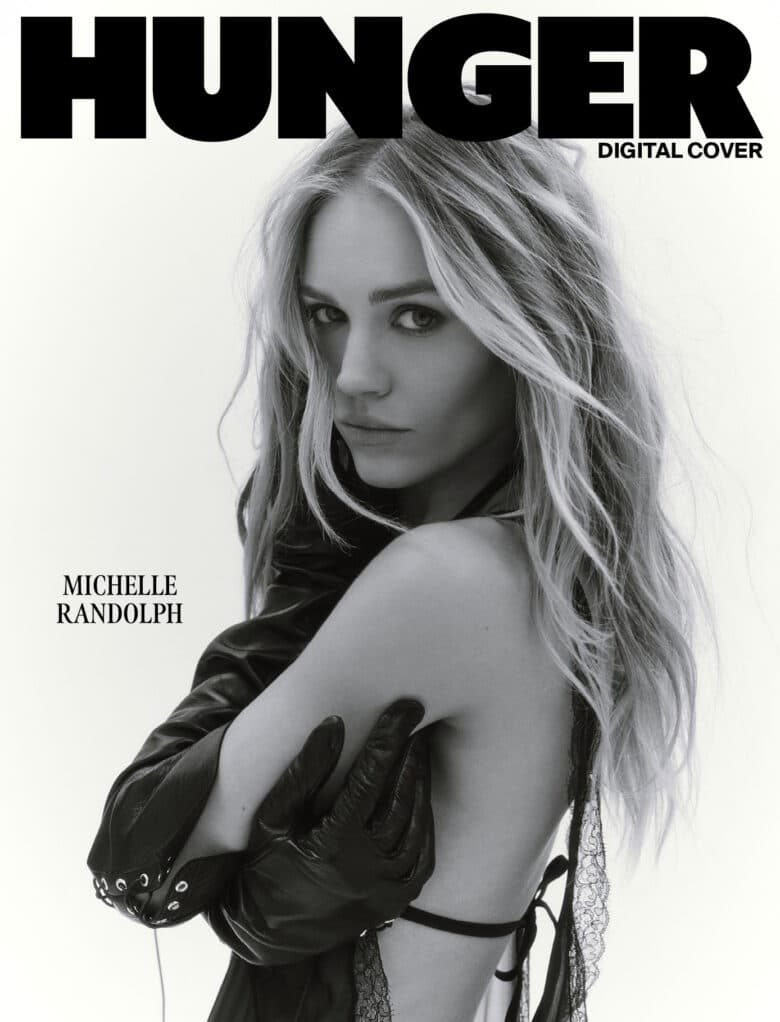

Taken from HUNGER Issue 27: Call to Action. Available to buy here.