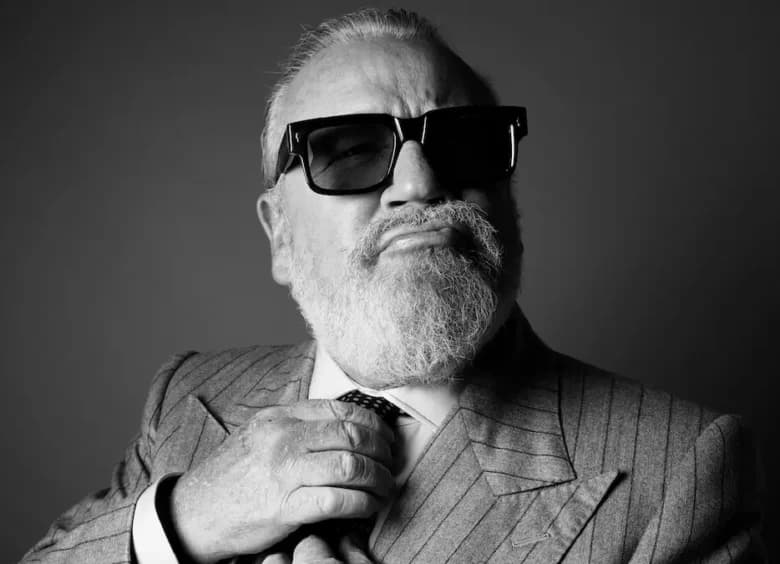

David Leon on his latest short film, ‘Stable’: “I see the North East as a brilliant microcosm for storytelling”

You’ll likely know actor David Leon for his on-screen appearances in ITV’s Vera, where he portrayed DS Joe Ashworth, the sleuthing sidekick to DCI Vera Stanhope for four seasons, before returning earlier this year in the show’s 13th season. The series, which follows Stanhope as she investigates crime in the local area of Northumberland, quickly became a must-watch in any British household, with audiences cultivating a soft spot for Ashworth thanks to Leon’s relatable and emotive portrayal. However, it’s not just on-screen in which Leon excels.

In 2010, Leon would make his directorial debut with Man and Boy, a short film starring Eddie Marsan that would go on to win the Best Narrative Short award at the Tribeca Film Festival. Then in 2012, he would release his second short film, Orthodox, starring Stephen Graham as an orthodox Jewish butcher who struggles to make ends meet and to care for his wife and son. Orthodox would also lead Leon to the release of his first feature film of the same name in 2015. Now, 14 years on from his directorial debut, Leon is gearing up to share his latest project with the world, Stable. The short film acts as a coming of age story, following the trials and tribulations of 18-year-old Conor (Charley Palmer Rothwell), who must fulfil the responsibility of taking care of his younger siblings following his mother’s death. Growing up in an economically deprived area of North East England, Conor’s life is engulfed in crime, but after pursuing a career in horse racing, his financial struggles could be about to be diminished indefinitely – but this comes with plenty of moral dilemmas along the way.

Here, we sit down with Leon to discuss his journey as a filmmaker and what we can expect from his upcoming project, Stable.

HUNGER: How did the idea for your short film Stable come about? Why was it a story that was important for you to tell?

David Leon: I’ve always been fascinated by the humanity which exists in characters who find themselves on the fringes, those who find strength in the most challenging circumstances. I’d read something which talked about how the racing industry were having to go deeper and further into parts of society to find workers for their racing yards, including prisons, by speaking to those who were about to be released into the world in the hope that they could serve as a kind of halfway house and provide rehabilitation. Brexit had left a labour shortage, and it being a job that young people no longer wanted to do there was a mutual benefit, it felt like a metaphor for the state of the nation and a succinct way of contextualising the class divide, with racing being known as the ‘sport of kings’. I went to a lot of race meetings and stable yards and built relationships to find characters who would build on that initial idea.

What aspects of Conor’s journey resonate with you the most, and why did you choose to explore the world of horse racing as a backdrop for his narrative?

DL: I’m intrigued by the idea of privilege and the concept of a glass ceiling given I come from a part of the country whose identity is so tied in with its working-class heritage. I’m drawn to the idea of how people’s experience of life can be so defined by the circumstances they are born into. How some are able to break free of their expectations and that lack of privilege, who are able to create their own path and not follow one that may have been laid out for them by their social and economic circumstances. For Conor, it’s a question of someone who has god-given talent but has never been given the opportunity to fulfil his potential and at the point he is given that chance is already battling demons which have accumulated over the life that he has lived to get to that point. He has siblings who depend on him and it then becomes a question of ambition versus responsibility and the idea of whether it makes him a bad person to have to sacrifice his family to follow his dreams or whether he should sacrifice his dreams for the sake of his family.

There’s a contrast that horse racing is this upper-class sport, and also one of exploitation that is seemingly going out of fashion… How much of this was deliberate?

DL: I was conscious that the racing would act as a metaphor for class and as an ethereal presence in terms of the way that Conor develops a spiritual relationship with an animal in a way he has struggled all his life with humans. Horses have been man’s best servant over the years, through wars, the industrial revolution etc. and there is a co-dependency that exists. We have depended on them over centuries and they depend on us for their survival. So to encapsulate that relationship felt like another layer that was important to take into consideration.

Do you relate to the character or Conor’s circumstances in any way?

DL: I think ideas always come from a somewhat biographical place and that’s often subconscious. Whether you like it or not you’re guided in some respect by your experiences and the things which make you who you are, and I feel that’s something to be encouraged. It always felt important for Conor to have a moral compass, in order for the character to feel empathetic. He makes bad choices at times, often defined by his own life experience and the tools he has acquired, but it’s usually with the bigger picture of doing good or trying to better himself in mind.

What is something you’d like people to know about Conor and about the film as a whole that audiences might not see at first?

DL: Stable was designed as a diptych, to sit alongside a companion piece Hyem (Home) which comes later. They mirror each other and we see how the circumstances of the first film have taken their toll and how, having given up on his dream, he tries to find redemption or atonement and eventually does so in a character whom he had previously thought of as being from the opposite end of the spectrum. Sometimes we judge others without having walked in their shoes. I think the idea that we might not actually disagree about as much as we think and by looking beyond people’s initial beliefs we can learn to be more tolerant and find common ground in our humanity is not a bad place to start.

Do you think there are enough conversations around real-life stories of hardship coming from the North of England?

DL: I see the North East as a brilliant microcosm for storytelling because it has such a strong identity, which is partly due to its geography. A collection of the furthest northern English towns and cities which have evolved in reaction to that. It’s not all hardship, there is a humanity and a deep sense of pride in the area, grounded in its industrial working-class roots. There is a warmth of spirit and an overwhelming sense of treating one another as equals. It feels under-represented though in terms of the presence of stories that reflect that experience. We’re used to seeing Northern stories set in Manchester, for example, which can sometimes be used as a generic symbol of all things North, but rarely on Television especially, do we see nuance within that. Ken Loach has made a series of films set in the region and I get the sense he goes back because it is so symbolic of the issues that profoundly affect us in this country. There are genuine experiences that are specific to individual towns and cities in the North which need to be told and want to be heard, which reflect what it is to live in these places specifically – and the meaning that comes from them being seen. They are by definition different from the experience of London for example.

More importantly, do you think people listen to them? Do you think they are amplified enough?

DL: Working-class stories are rich and varied and full of life and character. They are the lifeblood of our communities and they should be amplified wherever possible. One of the things that was important with Stable was to elevate the tone away from social realism but still be able to discuss those themes in the vain of filmmakers who have had the most profound effect on my life like Lynne Ramsay, Andrea Arnold, Alan Clarke, Ken Loach, Shane Meadows etc. – social realist with working-class stories at their heart and whose work leaves a legacy driven by their ability to so profoundly affect.

I think it’s important that culturally significant stories continue to be encouraged as they’re important in furthering the conversation and nourishing society. It’s easy to get drunk on entertainment and escapism – but I think people also want the issues of the day to be reflected in the stories they consume, to help them make sense of the madness of the world around them.

How would you go about explaining your creative process as a filmmaker?

DL: I suppose it’s driven by the needs of the project. I like to do as much research as possible and spend large periods of time immersing myself within whatever world it may be, meeting those characters and becoming as comfortable as possible in their circumstances. Getting a visceral sense of the world and how it looks and feels, but also to see what the texture of a new landscape for example says about the demands it places on the people that live within it. That’s important for the aesthetic and tone but it also acts as a guide to why characters are driven to live the way they do. At every step of a film’s process, people are looking to you for answers, and in order to have a vision that is authentic, you need to have gone into the long grass and come out the other side.

How do you approach balancing storytelling with conveying important messages or themes?

DL: I often think that the themes lead the story and the character for that matter. I think you have to be careful when talking about what’s important because I don’t see it as my job to be an educator. It feels more about asking questions than providing answers, but more importantly, it creates a feeling that perhaps drives an audience to ask those questions of themselves. So when we are emotionally affected by a story to the point where we can’t shake it and it stays with us for days or even years, that’s when it feels that films have the ability to truly move people and make a difference.

With your experience as both a writer and director, how do you navigate the creative process to ensure your vision is effectively translated onto the screen, especially when tackling sensitive or emotionally charged subject matter?

DL: It’s helpful to the writing process to know that you’re the person who is going to realise that transition from page to screen. I tend to think very visually although that’s not always helpful for writing because that is a discipline that has various rules which, granted, are there to be broken but you need to understand them in the first place and think about the visual can sometimes get in the way of what’s right for the story. But having spent a lot of time absorbing the world before the process starts, I find it helps to then realise that on the page with a sense of a specific location or character in mind which made you feel something, knowing that you have the foundation for the world you’re looking to build.

Do you ever feel like there’s a jump or a gap of sorts from what you pen down as a writer compared to what you create as a filmmaker? If so, how do you strive to bridge that gap?

DL: The leap from page to screen is a really interesting one and when you have control of both things you can define the aesthetic within the page so the leap is less felt or profound. When you are working with another person’s writing and the custodian of bringing that story to life it requires a different kind of approach because you have to get inside their head to start with before you can then begin to take something through the gears, elevate it and give it life. That’s a great responsibility and a challenge which I think is incredibly rewarding, particularly as part of a team who are all pushing to achieve the same thing and inspiring the process along the way.

What are the stories or characters that you are thinking more about; people, places or stories that you want to delve into more but haven’t yet?

DL: I’d like to explore something in a more conceptual way. I’m always drawn towards the execution and sometimes that can play into realism, but I’d be excited to adapt a novel for example that lends itself to a more elevated and surrealist approach, that subverts what an audience is expecting and allows for a more abstract telling. It feels like a period of time where there is growth and great change and to represent that in ways that push the envelope is exciting.

What do you hope people take away from your work?

DL: You just hope that the work affects an audience, I remember being at a screening of Jonathan Glazer’s film Under the Skin and being mesmerised by a scene, but at the same time noticing people were walking out. I thought, how is it possible that I feel so strongly one way and that these people feel the entire opposite, to the point that they want that feeling to end? It’s a great lesson about the subjectivity of filmmaking and life in general. If you feel compelled enough by something it’s likely you will find an audience that feels the same way.