Artist Alexander James on his short film about intergenerational storytelling

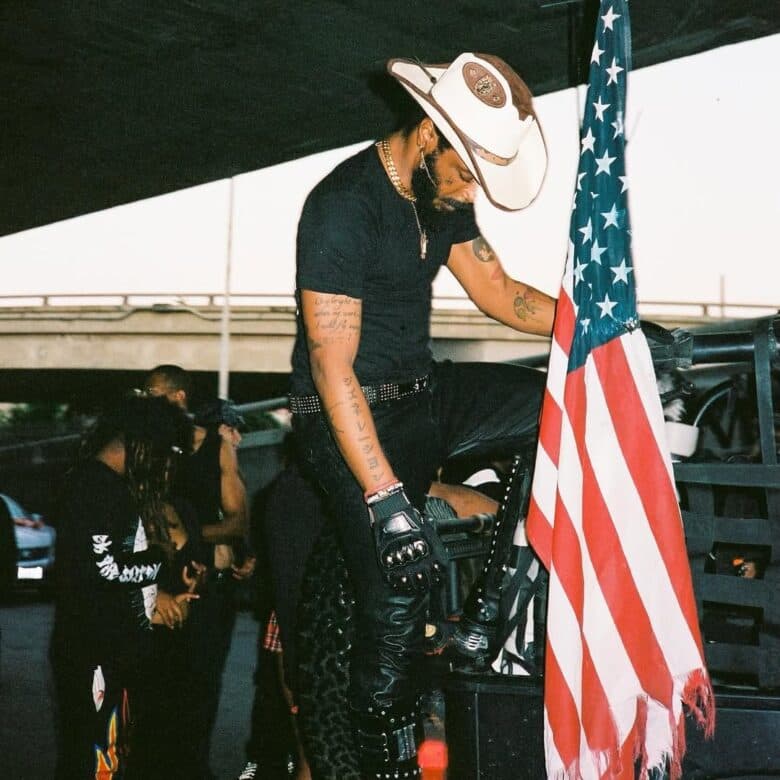

Alexander James has earned a name for himself thanks to his large-scale paintings — abstract, colourful and flirting with the human form rather than straight-up depicting it, they’ve landed him solo shows at Marlborough and Miami’s Room57 Gallery. But in his latest work, Smile, James takes an unexpected turn. While we still get to see him command the canvas, it’s another element of the short that grabs the viewers’ attention — the voice of his grandfather, Gerry Kaye.

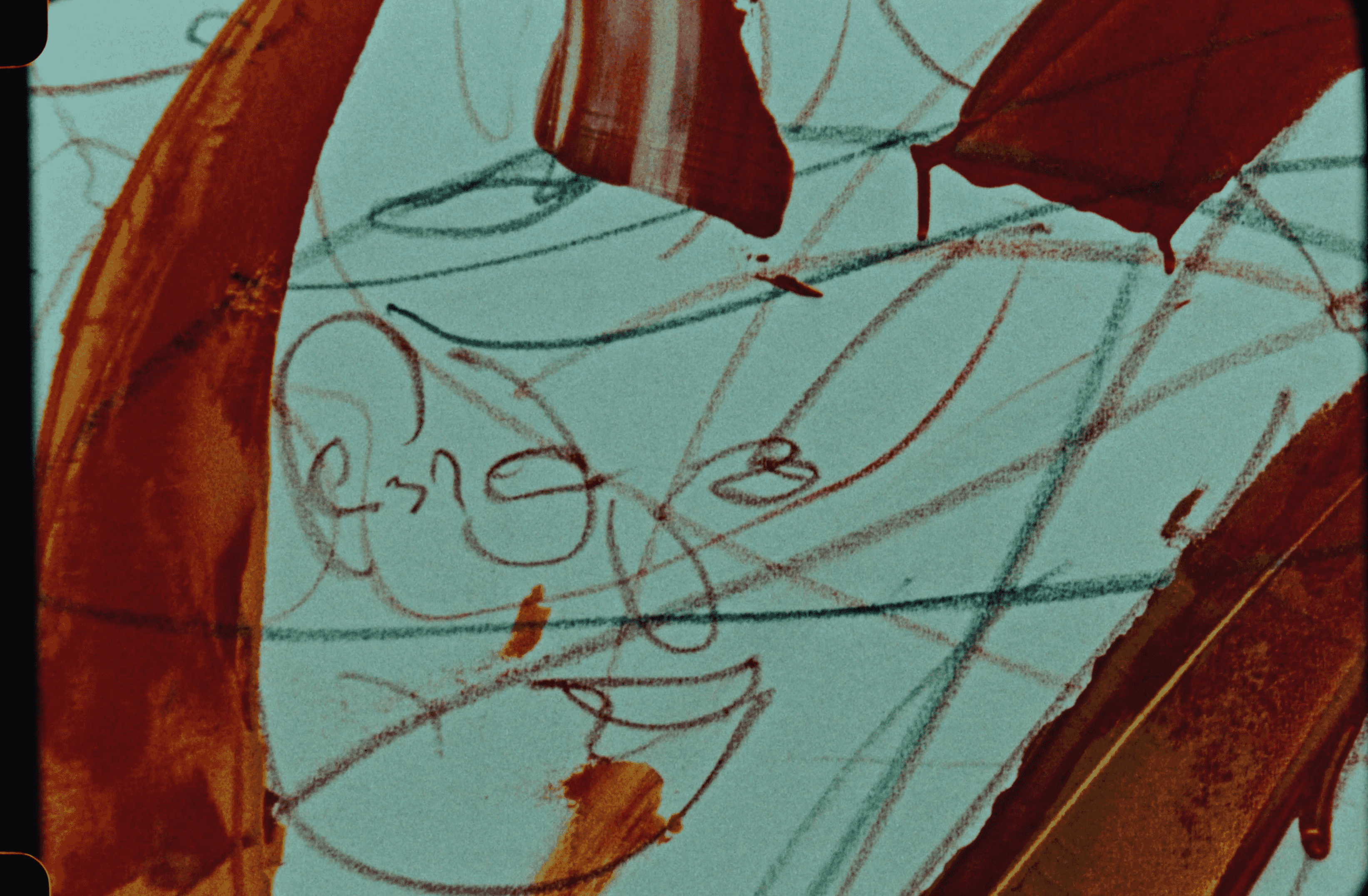

Stories of post-war London, family resilience, and life lessons wrapped in humor flow from Gerry into James’s work, intimately captured in Smile through both 16mm and digital footage. Splicing together scenes of James painting with grainy glimpses of city life past and present, the film does exactly what James values about the medium — its ability to “compress, expand and juxtapose moments in a way that’s impossible in other forms.”

Ahead of Smile‘s premiere at Ladbroke Hall, we sat down with James to talk about capturing memories on 16mm, the meditative quality of paintings, and why he asked his grandad to sing some Nat King Cole.

You’ve captured your grandfather through painting, recorded tapes, and now film. What does each medium reveal about your relationship?

Each medium helps reveal different facets of Gerry, our relationship, his life as I know it, and who he is from my perspective. It allows me to explore storytelling in various forms. I found tape to be the most raw and intimate and I’m looking forward to exploring this medium more.

The film shows you painting while he talks. How different is creating with his voice in the room versus from memory?

When his voice is in the room, he becomes a collaborator in the act of creation. His words, tone, and presence influence the strokes during the painting. There’s a level of intimacy in the air. It can really dictate decisions such as palette choice and subject matter.

Your grandfather’s stories span post-war London to today. How do those different Londons appear in your work?

The London of his time feels raw and resilient, shaped by the aftermath of the war and the grit of daily life. This may appear in my work through a sense of nostalgia and a focus on textures. Today’s London feels like a mosaic of identities, fuelled by change. It’s fast-paced and diverse — this is an important feature in the movement of my artworks.

There’s something powerful about filming in your studio — it’s this space where past and present collide. Was that the natural setting?

The studio can either be a charged space or the complete opposite. And filming in the studio is very personal — you’re inviting the tension between past and present to seep into the work. But it’s a grounding home for the narrative and subject to eventually turn into something real.

The film uses both 16mm and digital — was that about capturing different kinds of memory?

I found 16mm, being grainy, feels more intimate and nostalgic. It’s a great way to keep a memory preserved. This was something we were trying to portray in Smile. It can evoke an archival quality, as if you’re watching something deeply personal or rooted in history. This felt appropriate for the conversations we were having with Gerry about his dreams and fragmented memories. We used digital for other moments in the video — for capturing immediate moments once ideas hit.

Your paintings often incorporate letters and photographs. How does film handle these physical fragments of history?

Paintings allow viewers to absorb these objects in a still and meditative way. Film can animate them in a different context — not just literally, but emotionally. It’s exciting jumping between these worlds.

You talk about stories being “lessons in disguise.” Has making this film uncovered new layers to those teachings?

Absolutely. Stories often begin with a core idea, but as you bring them to life, you start to discover subtleties you might not have considered.

Your work plays with time, mixing ancient and recent history. How does film let you explore that differently?

Film is a great medium for exploring time because it allows you to compress, expand and juxtapose moments in a way that’s impossible in other forms. Through editing and sound, you can make the ancient feel immediate and the recent feel timeless.

Working with the directors of Smile, Robin Hunter Blake and Laurence Hills, on this… How did other perspectives help tell such a personal story?

Collaborating with Robin and Laurence was a truly special and seamless experience. We worked effortlessly together, with ideas just flowing naturally between us. Their perspectives added immense depth to the narrative and our visions were perfectly aligned throughout the process.

Tell me a little more about the title of the short?

The title came about during a two hour phone call with my grandfather. I asked him to sing his favourite song, already knowing that I was about to hear “Smile” by Nat King Cole. It summarised the painting process and video process so perfectly and made the most sense.

Your art often blurs conscious and unconscious experience. Does film capture that space between memory and reality differently?

It has its own way of capturing that space. I have found that film has the ability to reshape time, space, and perception.

This premieres at Ladbroke Hall. How important was finding the right space for these conversations?

It was incredibly important and we explored so many options. But the moment we saw Ladbroke Hall, we were blown away. It felt like a scene straight out of the film.