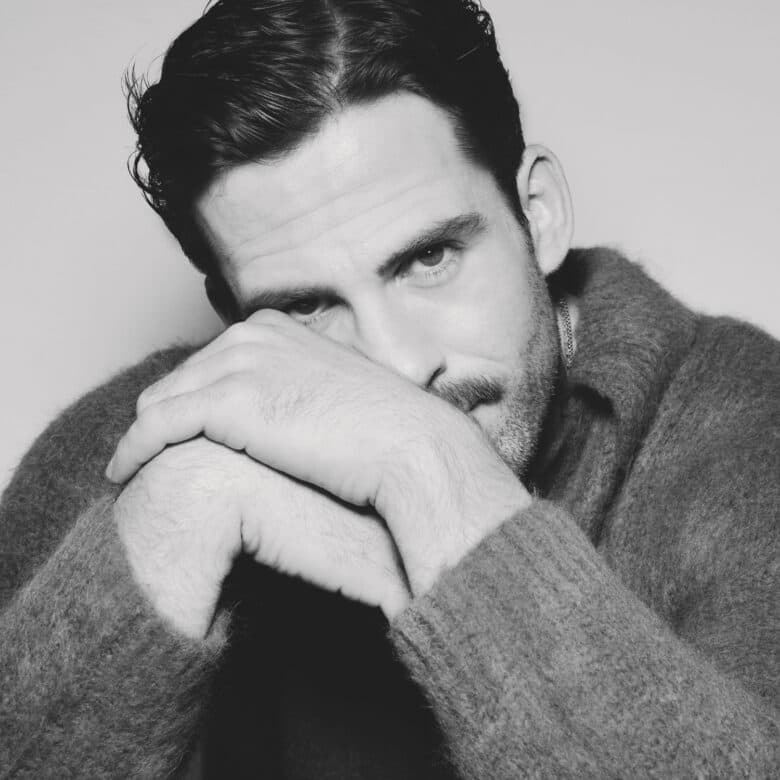

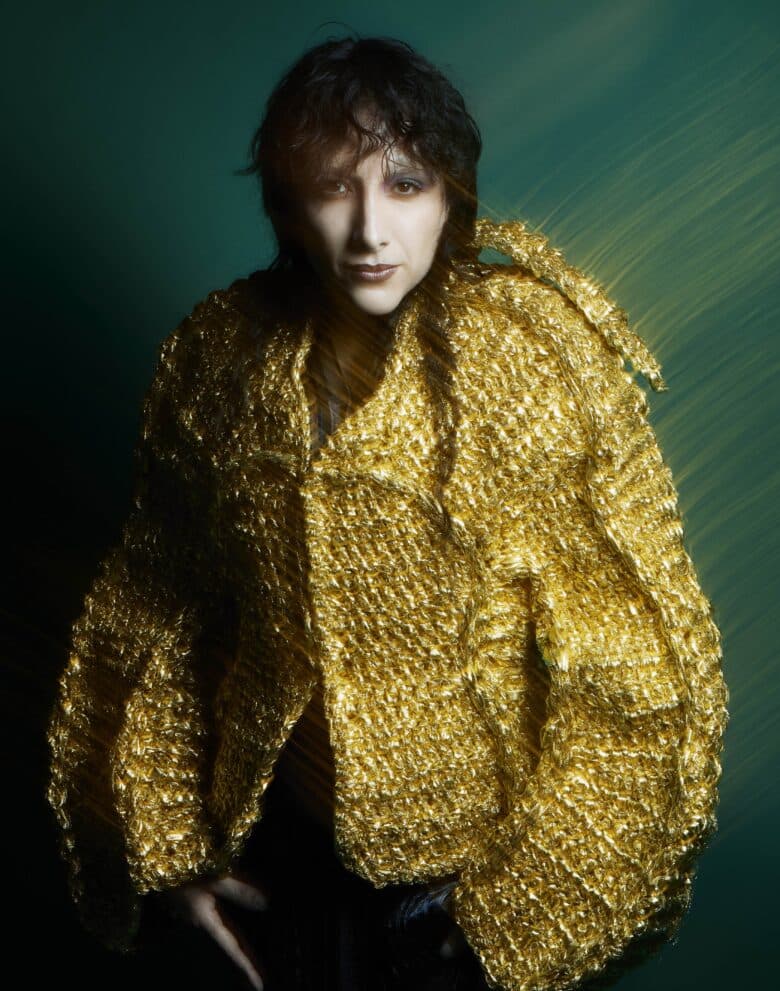

Mason Alexander Park is making a mess of history

There is something deeply entertaining about talking to Mason Alexander Park at a time when they are (voluntarily) screaming themselves into emotional ruin eight times a week. Oh, Mary! — the feral, ahistorical fever dream currently tearing through the West End — demands that Park spends 80 relentless minutes unraveling in public. By curtain call, they are peeled out of wigs and period petticoats, exhausted and exhilarated. It takes a rare kind of control to make a mess look this good, but for Park it seems like second nature.

Written by Cole Escola, Oh, Mary! imagines Mary Todd Lincoln as a fully unleashed problem that’s narcissistic, wounded, hysterical, desperate to perform and determined to be seen. The play is obsessed with the excess of feeling, repression and desire, with the strange liberation that comes when things finally boil over. What could be more fun than being monstrous and lovable without explanation?

When we speak, Park moves easily between veritable cultural phenomena — the politics of British theatre etiquette; the radical potential of campness — and smaller, more practical frustrations, like the ongoing struggle to find a genuinely good salad within walking distance of the theatre.

Roisin Teeling: Oh, Mary! is inspired by history, but what did it feel like when you realised you’d be stepping into this version of Mary Todd Lincoln?

Mason Alexander Park: It’s the greatest thrill to know nothing about someone, and yet be in a piece that’s so confidently presenting a version of her. I know the Mary Todd Lincoln from the play because she’s so brilliantly written and three‑dimensional, but she has none of the reality of who Mary Todd Lincoln was as a human being.

There’s a real joy in taking a small piece of information from history that people vaguely know, and then riding a plane that has absolutely nothing to do with that reality. This isn’t like Hamilton, where you’re still attempting to be rooted in history even while theatricalising it. It feels much closer to being asked to play a completely fictional character, like The Tempest or Cabaret.

“I have to have a full mental breakdown for 80 minutes.”

RT: The show is chaotic and relentless, and you’re doing it eight times a week. What does it actually take to sustain that?

MAP: A lot of discipline. Performing always does, but this show in particular has a frenetic energy and a chaotic attack that requires total confidence and stamina from everyone involved.

Even though we’re well into the run now and it’s a well‑oiled machine, I still have moments where I think, ‘God, this takes a lot out of me’. For the play to work the way I want it to work, I have to go out there like a screaming banshee and have a full mental breakdown for 80 minutes. That’s what gives the audience the payoff, that operatic feeling and that sense of excess.

It’s joyful, genuinely. I love doing it. But it also requires knowing yourself as a performer and understanding what you need to do throughout the day to show up properly at night.

RT: British theatre etiquette has a reputation for being reserved. Were you surprised by how people responded?

MAP: I’m surprised every day. If you do this play in America, really anywhere, people aren’t necessarily afraid to be loud or boisterous. Here, you sometimes need one silly gay person in the front row laughing early on, and suddenly everyone understands that they’re allowed to be as big as they want.

Those nights are remarkable — you can feel the whole audience let go. Last night, we had people booing one of the characters. It’s fun to think that the audience is taking that much ownership of the experience. They really are showing up and being loud, silly and queer.

“You sometimes need one silly gay person in the front row.”

Every now and then, you get a grumpy couple who are disgusted by the open queer energy and can’t allow themselves to enjoy the silliness of the play. They’re allowing something more political to block them from enjoying themselves, and that’s always a sad moment. You can see how close they are to joy, and how much they’re denying themselves by judging the people around them instead of letting go.

RT: Is there a post‑show ritual?

MAP: Honestly, my biggest struggle in London has been when I’m craving a salad. In LA, you’re never more than ten minutes away from a really good grain bowl. Farmer J’s has weaselled its way into my heart, it’s just not close enough to the theatre.

RT: Does any part of Mary feel familiar to you?

MAP: I’ve got to love her, but she has a lot of faults. She’s an aggressive, wounded animal and so her reactions are unpredictable and intense, but she’s also deeply relatable. Mary wants to return to the stage, she believes she belongs there. Every artist understands that feeling of knowing you’re meant to do something and not being given the platform. That belief, ‘I belong here, this makes me happy’, is powerful, even if the world doesn’t agree with you. Mary has been forced into a box by the people around her, and she’s clawing her way out, hurting others in the process. That comes from a very personal place.

RT: Queerness and camp are often dismissed as ‘too much’. Do you think that idea is something the play is engaging with?

MAP: I know from hearing Cole Escola [the writer and first actor to play Mary] talk about their process that being ‘too much’ was very much at the forefront of their mind. I believe they had something written on their dressing‑room mirror about being annoying and being loved, something like, ‘Can you love me if I’m annoying?’ And I think a lot of people relate to that.

A lot of people are told they’re too much, especially in this business and especially queer people. The play is asking the audience to fall in love with someone who’s a bit of a menace — a kind of Tasmanian devil, a tornado of a human being, incredibly annoying, kind of mean. And yet everybody’s rooting for her, because we can all understand what it might have taken to get her there.

So yes, I do think the play is engaged in a conversation about being too much. But I don’t necessarily think audiences come in thinking, ‘This is going to be too much’. Most people walk into the theatre knowing it’s about Mary Todd Lincoln and that’s about it. In that sense, it really is an assault.

RT: Do you think this silliness can be radical in its own right, especially now?

MAP: It feels necessary. The world is in such a dark, painful moment that we need silliness to recharge. The greatest gift I can give anybody right now as an actor is laughter.

As much as I love drama, and as much as I’d love to be in some Oscar‑bait indie film, and those stories are important, I think it’s equally important, if not more so, to give people collective laughter. It helps people recharge and hopefully approach the next day with a little more joy, or a little more radical optimism.

At the end of the day, this play is so fucking stupid, and also so healing. The amount of people who come to the stage door and tell us how badly they needed that night is really moving.

“This play is so fucking stupid, and also so healing.”

RT: You’ve spoken about how radical it can be to exist onstage without having to explain or justify your identity. What does that freedom feel like in Oh, Mary!?

MAP: It really proves that actors are actors. Throughout theatre history, people of various genders have played all kinds of roles — it’s ingrained in the art form that gender is something playful.

Obviously the world has changed. Trans people are hyper‑fixated on in a negative way, especially in this country, so you do have to be conscious of the moment you’re presenting work in. But for me, growing up, I always dreamed of being a leading lady, and to arrive at a point where that’s not only true, but it’s in a role that has nothing to do with my identity. That’s incredibly liberating.

With something like when I played Hedwig in Hedwig and the Angry Inch, the role is inseparable from conversations around gender. But Mary Todd has nothing to do with that. She’s just a menace. I’ve never had to compromise my identity to be onstage, especially on the West End, and that feels like a real feat.

RT: You’ve played Shakespeare characters, you’ve played Mary — which role has been more exhausting?

MAP: Mary is one of the most exhausting roles I’ve ever played. She’s rarely offstage, and the whole play hinges on her leaning forward the entire time.

Hedwig was also one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. Cabaret required a lot as well. And Shakespeare carries a very different kind of demand. When I did The Tempest at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, it was my first time working with Shakespeare professionally. The last play staged there had been The Tempest in the 1950s, so it felt like a huge return. Sigourney Weaver was my Prospero. It was a really spiritual experience.

“Growing up, I always dreamed of being a leading lady.”

What’s surprising is that Oh, Mary! is somehow harder than all of that. It should be easier. It’s sillier, lighter, less emotionally torturous, and yet I find it incredibly difficult — which is kind of wonderful. It’s nice to be challenged.

RT: What do you hope audiences feel leaving Oh, Mary!?

MAP: Lighter. And maybe with the understanding that repression gets you nowhere — it just bubbles up and turns you into something you don’t want to be.

RT: Who’s a camp icon you trust with your life?

MAP: Liza Minnelli, come on. There’s a little bit of Liza in everything I do.

RT: And finally, who’s a historical figure you’d love to misbehave with onstage?

MAP: Albert Einstein. I loved him when I was growing up. I had that picture of him with his tongue out on my wall. There was once a world where I thought I could be a scientist. That clearly didn’t happen. But I think he got into some weird shit.

- PhotographerRankin

- StylistAlice Secchi

- WriterRoisin Teeling

- Make-Up ArtistGuy Common

- Hair StylistLewis Pallett

- ProducerKay Riley

- Photographer's AssistantsCharlie Cummings, Jasper Abbey

- Fashion AssistantClaudia Vargas Fernández

- Make-Up AssistantRashida Blair

- RetouchingFTP Digital